Amy Thompson was the winner of the Scholars’ Prize in Architecture in 2021–2, spending three months in Rome.

In this blog post, Amy reflects on the research conducted during her residency, which was focused on the Nasoni (drinking fountains) in Rome and how they impact the community. She considers how her time in Rome helped strengthen her understanding of space, in turn supporting her projects in South Africa as Director of Yes& Studio, and her ongoing work at Europe, a settlement in Gugulethu.

When I think about the city of Rome, I can’t help but think about water. It is such a ubiquitous presence within the urban fabric of the city that Rome has been nicknamed La Regina dell’Acqua. On my visits to the city I have marveled at the seemingly endless abundance of this resource and left in awe at the spectacular fountains, gushing water and gigantic chiseled marble figures nestled within the city’s fabric.

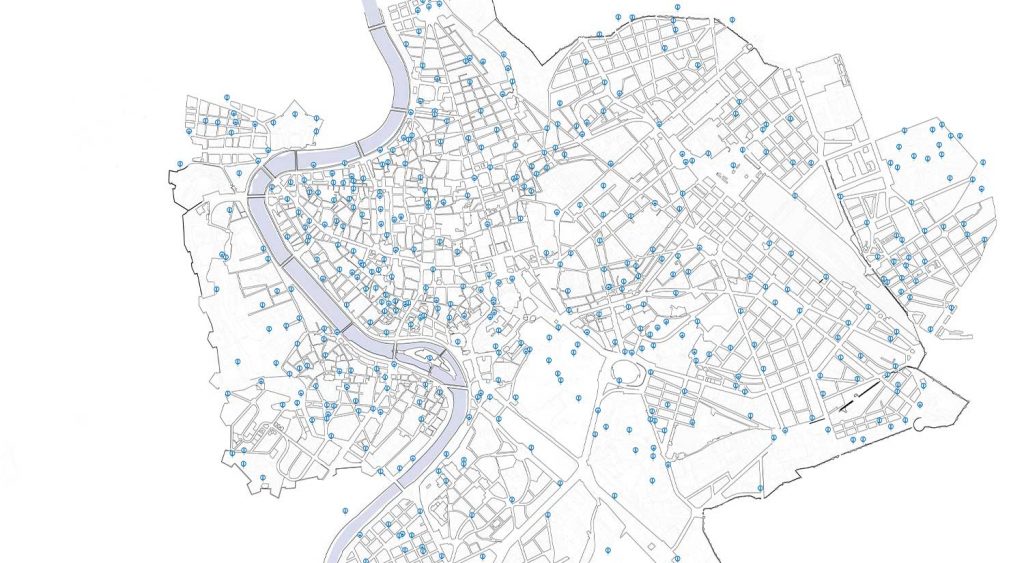

However, in reading more about this resource I have found that, whilst much focus and attention has been paid to the aqueducts and water points of ancient Rome and the reconstruction of these systems to create the decorative fountains of the Baroque, there is little focus on majority of the 2500 water supply points currently in operation [1]. These are simple drinking fountains called Nasoni, scattered through the city and often simply placed on a kerbside or building edge. These fountains present the domestic face of La Regina dell’Aqua and offer a pragmatic departure point to understand the city speaking to the connection between home, domestic tasks and public space.

The Nasoni, largely unchanged in design since their introduction in 1872 [2], are 1m high columns which get their name from their characteristic “large nose” water spout. They are free flowing offering a seemingly endless access to drinking water and at the peak of their popularity, there were approximately 5,000 in Rome and whilst their number has dwindled as domestic water connections have become commonplace, there are still more than 500 within the historic city core alone.

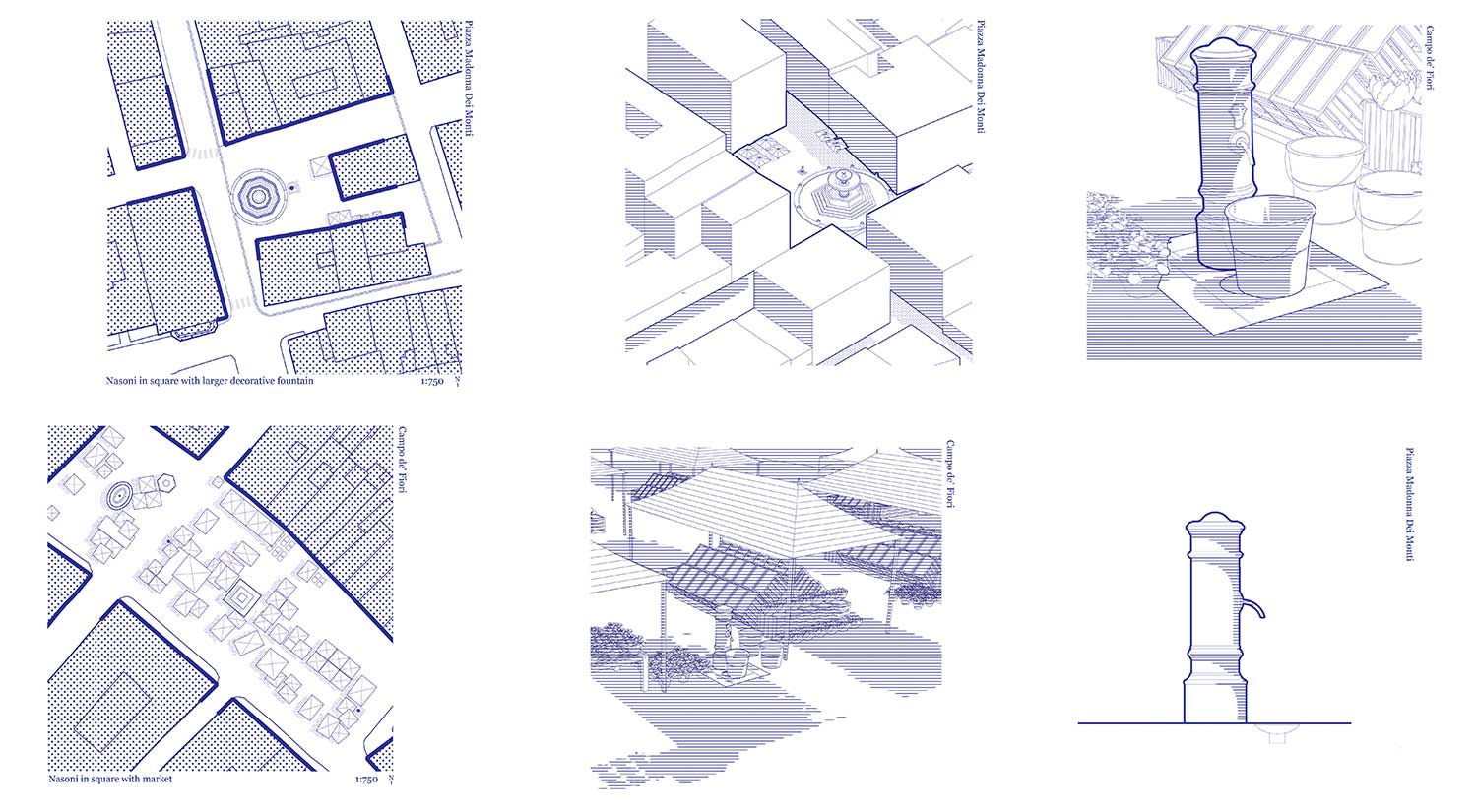

My time in Rome was spent walking the streets, squares and parks mapping these water points. Google Maps tells me that I walked a total of 600kms, a habit I supported with a daily intake of gelato and coffee. My embedded research allowed me to categorise the water points by age, type, and most importantly by spatial characteristics, revealing the important role these water points play as space making devices.

Potentially the most interesting spatial typologies are the Nasoni in squares and streets used in conjunction with markets and trade. In these spaces the Nasoni are used to wash fruit, keep flowers hydrated and to clean out the squares when the markets pack up at night. This highlights the persistent usefulness of these waterpoints, which caught me by surprise. I fully expected to find the Nasoni to be a cute tourist quirk; a remnant of a time gone by, but they endure to service all residents of Rome. The water provides some dignity to those without a home, supports small businesses, tourists and residents.

When there was a drought in 2017, Acea (the water company responsible for the nasoni and the water supply) started shutting the nasoni at a rate of 30 a day.[3] The push back was visceral, particularly from groups working with the vulnerable. It was revealed that there is actually relatively little water lost through the system and that the ever running nasoni actually serve a dual function to alleviate and reduce pressure on old pipes, essentially venting the system and preventing leaks and flushing the system, preventing smells.[4]

My time in Rome offered an opportunity for personal and professional growth and collegiate connection. The chance to be immersed within a city of such rich and varied histories allowed me to strengthen my understanding of place. The opportunity to live in Rome over the three month residency has helped me better understand the link between public space and public infrastructure which will support projects undertaken in South Africa where I work in complex informal environments where there is a critical need for both positive public place and infrastructural services.

Water follows the same physical laws and satisfies the same needs regardless of location. A great deal of my interest in studying the water systems of other cities stems from my work in Europe, an informal settlement in Gugulethu, which I have extensively studied and worked in since 2014. First, as the site of my masters dissertation that explored ways of delivering in situ informal settlement upgrade and attempted to recognize settlement making as real time city building. Second, with Dr Julian Raxworthy as the lead of a multi-disciplinary research team that used decorative gardens as a lens to explore lived experiences and finally in a real bricks and mortar upgrade (funded by the Rotary Foundation) that puts some of my thesis premise into action.

Europe’s experience with water is immediate. Like many informal settlements it is prone to devastating winter flooding. There is no formal storm water or sewer system on site and runoff drains out of the settlement along makeshift pathways. Portable water points, 1 per every 40 people, are used for household consumption and laundry and are scattered along these pathways, which makes them accessible but since they often break or leak this adds to the water runoff problem. This Drainage results in muddy walkaways which are sometimes contaminated with solid waste and pose a serious health and safety hazard.

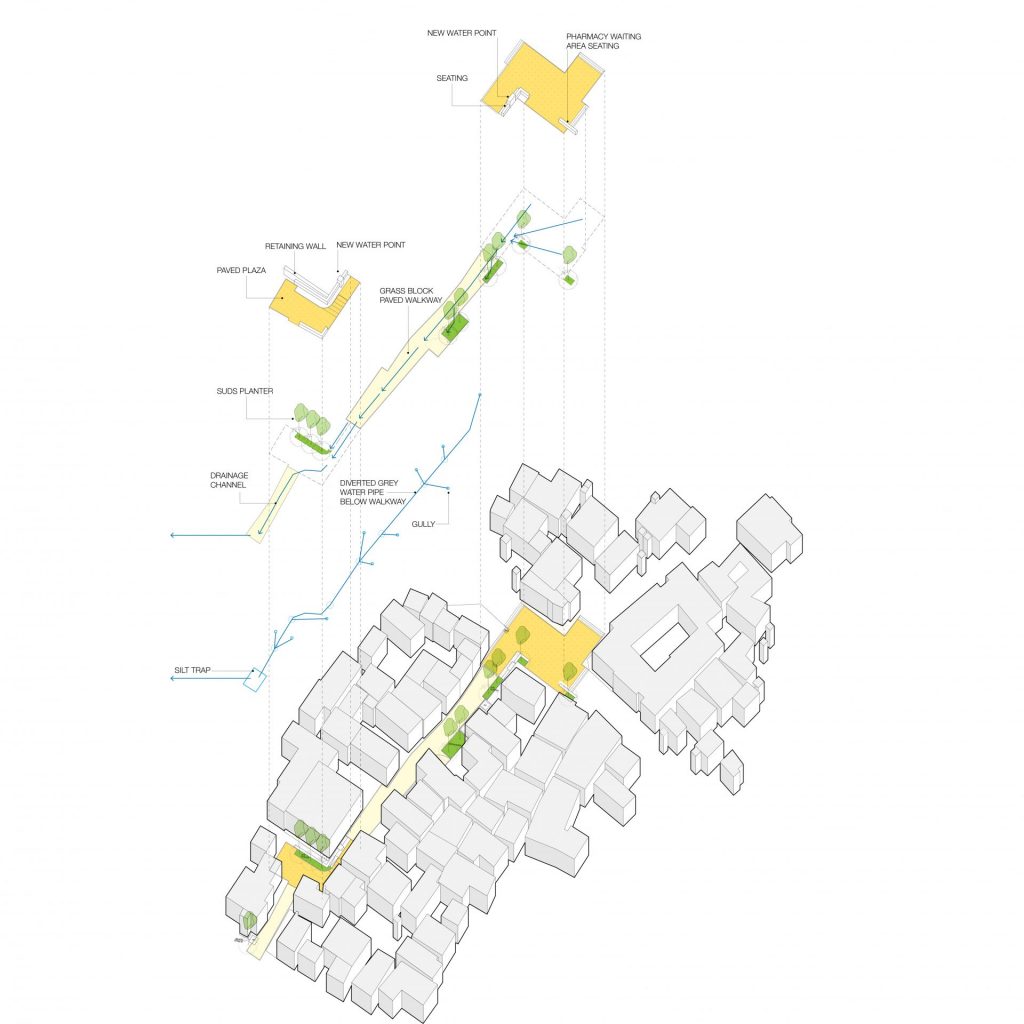

Our project attempts to reframe infrastructure as a public good and reimagines the provision of services to contribute to the public spaces in the settlement. The intervention stretches from the primary pedestrian access route to the settlement to the key intersection which has identified as an emerging commercial and community node, with a large creche, a pharmacy and several spaza shops.

The intervention capitalizes on this existing activity by inserting a new public space associated with the waterpoints. These public spaces connect to a newly paved walkway, that doubles as a stormwater channel. A grey water diversion system developed with JG Africa (a firm of engineers) was introduced underneath the walkway to reduce contamination and to improve health. I have been studying and observing the waterpoints in the settlement for some time. Our project sees us upgrade two of these. We have included simple and robust laundry platforms that doubles as seating for the square and will hopefully provide a well surveilled and safe space for women and children.

In such environments resources are scarce and there is a general emphasis on the provision of engineering responses that directly address site and social ills whilst leaving the quality of public space unaccounted for. Through exploring the place making techniques within Rome I have been able to add to my design understanding and begin to support my case for multi-functional community interventions that combine infrastructure provision with place making interventions.

[1] https://waidy.it/en/voice-from-city/rome-drinking-fountains.html

[2] Mauro, Fabrizio Di (2009). I nasoni di Roma: e le altre fontanelle (in Italian). Editrice Innocenti.

[3] Lyman, Eric J. (2017-07-14). “News Analysis: Rome faces criticism as trying to save water by closing “big nose” fountains”. Xinhua. Archived from the original on August 8, 2017. Retrieved 2017-08-04.

[4] Interview with Waidy Wow team, Barbaro Francesco Saverio, 11 July 2022.