An interview with Jo Stockham, the Ampersand Foundation Fellow, in which she speaks about the work she has produced during her residency at the BSR from April–June 2022, ahead of the June Mostra.

Your work is open to a wide range of processes and materials, like architecture, printing, sculpture, as well as many present themes like feminism, materiality, technology. How are you putting together these multiple aspects of your research in Italy?

I work with two alternating currents; making images, writing and playing technically with materials processes, space, and learning about languages and histories which have been buried or hidden but might be helpful to negotiate the present.

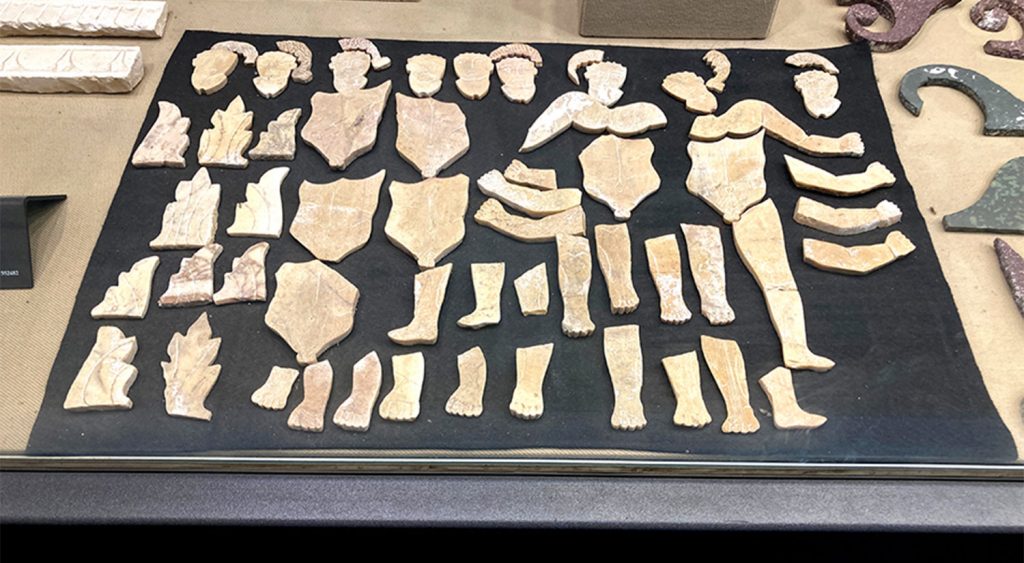

These urges pull one in different directions, but they come together through a process of constant comparison and juxtaposition. Rome is a very material city and working practices of early artisans such as these pieces of marble inlay from 2nd Century AD in Villa Dei Quintili seem very familiar to me as I use stencils and repeat images.

2nd century AD mass production, Villa dei Quintili

I first came to Rome with students from Cambridge in the 1990’s when teaching architecture there from the perspective of an artist who handled materials. It’s amazing how memory is activated by revisited space, though my initial visit was so brief. Visiting sites together is an ideal form of interdisciplinary research because discussion flows from a newly shared experience informed by experience, curiosity and the different specialist knowledges of the whole group.

In Pompeii I was reminded of the recent eruption of the volcano in St. Vincent, the small Caribbean island where my mother was born. Being told that it was ash not lava which caused the disaster in Pompeii was a shock bringing to mind images of ash covered Vincentian streets on the news. Visiting artist’s studios in Centocelle we discussed the benefits of collectives and the effect of property prices on community structures, something which has driven many artists from London in the last 10 years. Trinita dei Monti was a revelation. The extraordinary anamorphic paintings and exquisite sundial calendar in the monastery of the minims was made in semi-secret to avoid the censure of the church for venturing too far into science and mathematical speculation, clashes between faith and science which still have ramifications today.

Left; 17th century hand painted astrolabe/sundial; Emanuel Maignon, Triniti dei Monti. Right; Anamorphic painting of St Francis of Paola who founded the minim order

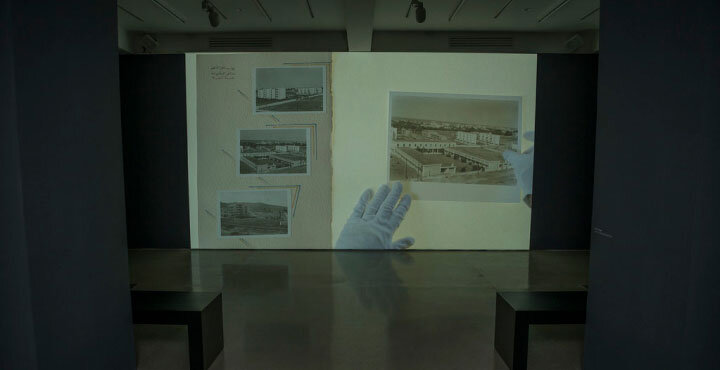

I am trying not to over determine the shape of my work. In the last session I was working with found marbled papers in this session I started making my own and learning the craft of marbling which is very error prone and affected by heat which weakens the surface tension of the water. Through digital printing and scanning I am expanding these patterns and thinking about the slippage between book, screen, real-world.

My first marbling experiments May 2022

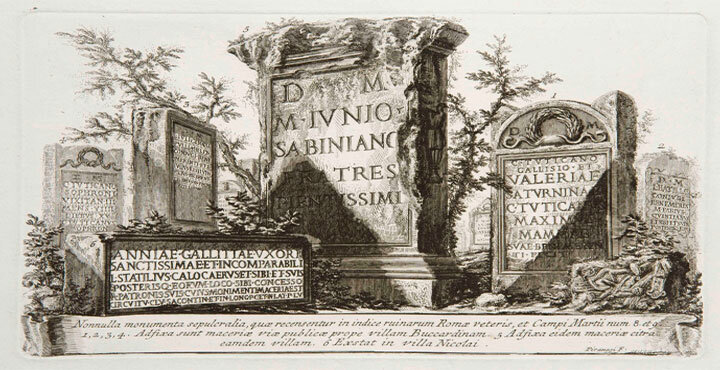

Marble is a metamorphic rock, made through heat and compression, but it is also a metaphoric rock with swirls of stories, myth and history embedded in its mineral structure. Marbled paper is made by floating ink on cold water thickened with seaweed, the ink expands and drifts. I enjoy the contradictions in this way of coming into being. The ever presence of marble in the streets, buildings and design consciousness of Rome is dependent on technologies and labour of many kinds over centuries and across continents. The reuse and movement of fragments of former buildings or monuments is common in Rome, Spolia (thinks also of the spoils of war) shapes the city. The various methods of collage I use in my work are a sideways link to these phenomena.

Researching marble has unearthed the term ‘lithic’ imagination. The seeing of images in marble, as in clouds, has a long history and is echoed in Betsy Wing’s translation of Édouard Glissant’s Poetic of Relation, prefaced with his phrase ‘I build my language with Rocks’ which starts with a discussion of myth and the epic referencing some of the things I have been reading such as Dante’s Divine Comedy, a text which every Italian has some knowledge of. The once liquid nature of marble is present in many samples such as these from the base of a column. In a dark church interior of mainly painted marble, this appears like a window to another world of light and air away from the gloom.

Base of a marble column. Basilica dei SS. Ambrosia e Carlo, Rome

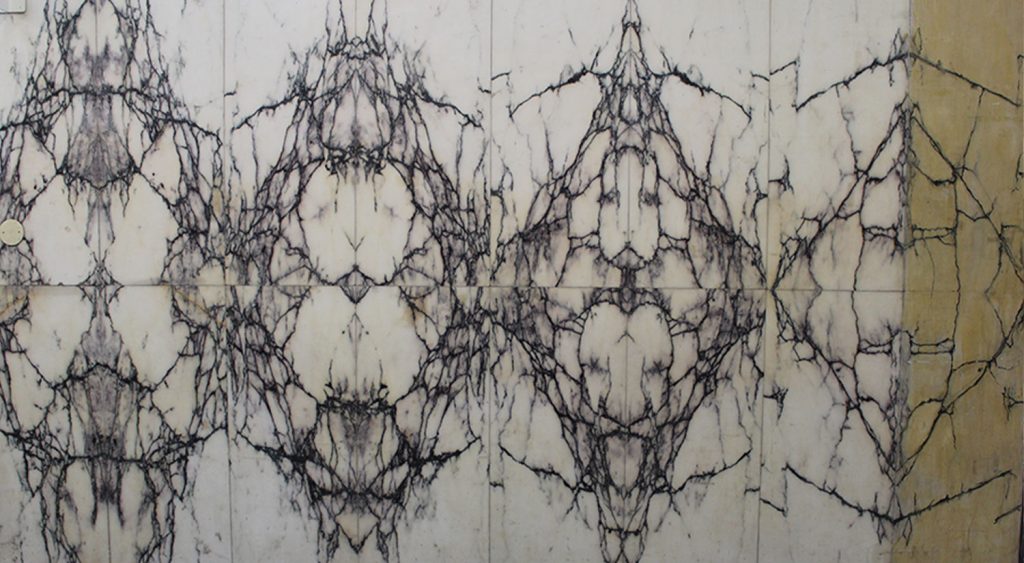

So-called book-matched marble, which comes from splicing and turning a sheet of stone, is everywhere. The use of marble to create a narrative as direct as the monk in turmoil below, is less common.

Left; Book-matched Marble EUR. Right; Lithic Imagination 2 Santa Maria D’Araceoli, Rome

You’re interested in researching about Italian artistic movements such as Futurism or Arte Povera. What interests you about them and have they got any point of connections with your work?

In the 1980/90’s I worked in public galleries in London leading education workshops for school and community groups with other artists. Michelangelo Pistoletto: Oggetti in meno (Minus Objects) 1965-1966 was one show I worked on at Camden Arts Centre in 1991. It profoundly influenced my teaching and aligned with my interests in the everyday and so-called art/life boundaries. I loved that fact that every rule Pistoletto made for a sculpture one day he broke the next. The works include found materials and models of social relations or domestic situations such as ‘Lunch Painting’ a wooden diagrammatic frame of tables and chairs.

The use of found materials was both a financial necessity when I began making sculpture and also a choice due to an interest in bricolage and the everyday. A trouser leg cannon I made in the 1980’s was in an exhibition about Arte Povera at the Estorick Collection in London (2017) curated by BSR fellow Roberta Minnucci who recently gave a fascinating BSR lecture on materiality.

The use of text in art really fascinates me but Futurism was not something I was interested in before coming to Rome. I reacted against the denigration of women and a fascination with war and speed present in Marianetti’s manifesto. But developing a more complex sense of the relation between modernity and language in Italy is important to me. Coming across the work of Rosa Rosà, Florence Henri and Bendetta in this year’s Venice Biennale gives me a way in to explore parolibera.

Glitch Feminism by Legacy Russell, a very different generational manifesto for collage and difference and Sally Rooney’s Beautiful World Where are You? where a character visits Rome on a writing fellowship have also shaped my sense of being here.

Awareness of translation and understanding the nuances of language as it is used, are key to living outside your own language and learning a new one. Jhumpa Lahiri’s book In Other Words has been a companion as she writes so beautifully about doubt and learning Italian;

‘When I discover a different way to express something I feel a kind of ecstasy. Unknown words present a dizzying yet fertile abyss. An abyss containing everything that escapes me, everything possible.’ pg. 45

Such estrangement from one’s habits of communication can be a chance rethink histories and language itself. Words have shape, weight and texture when you don’t fully understand them, their thingness, sound, shape and musicality come to the fore.

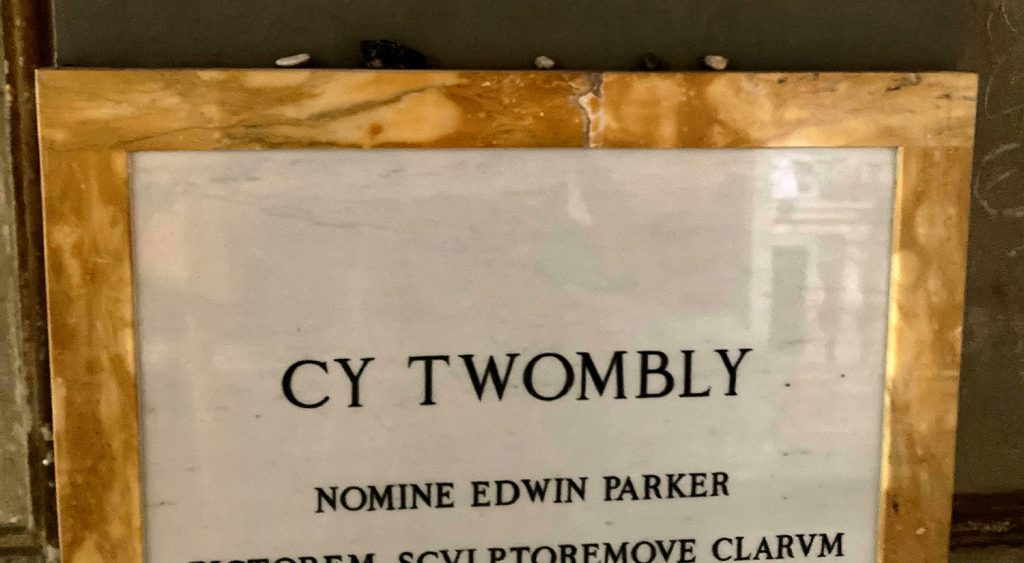

In a history of the BSR I read that Henry Moore felt he discovered ‘tenderness’ in Rome and was unable to return to the same way of working when he returned home. One very hot day I escaped the heat by wandering into La Chiesa Nuova to photograph some marble. Leaving I had a chance encounter with a memorial to the painter Cy Twombly. Visitors have left tiny stones as tributes – soon a small marbled stone will be joining them.