An interview with Hiba Alobaydi, Giles Worsley Rome Fellow, in which she speaks about the work she has produced during her residency at the BSR from September – November 2023, ahead of the Winter Open Studios.

The BSR residency is giving you the chance to visit and study the Mosque of Rome. Could you please tell us more about this project?

I applied for the British School at Rome’s Giles Worsley Fellowship because I felt passionate about pursuing a line of enquiry which developed during the past couple of years through my participation in a special pilot project between the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) and the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A), London, called ‘Surfacing Stories’.

‘Surfacing Stories’ – which debuted during the London Festival of Architecture earlier this year – aims to draw out forgotten or overlooked narratives from within the V&A’s Architecture Gallery. Each of the selected participants, including myself, were asked to act as ‘Critical Friends’ and re-write a label for an object within the collection. I chose to re-write the pre-established narrative of certain objects ripped from the Alhambra in Spain and called into question both the West’s assertion as the most important arbiters of architectural taste as well as the pre-dominantly Eurocentric celebration of Islamic architecture and design. However, I was also intrigued by the Alhambra’s diasporic Islamic style.

So, once the BSR’s call for submissions was announced I started researching the history of Islamic architecture in Rome which is how I came across the Moschea di Roma/ Mosque of Rome and Islamic Cultural Centre.

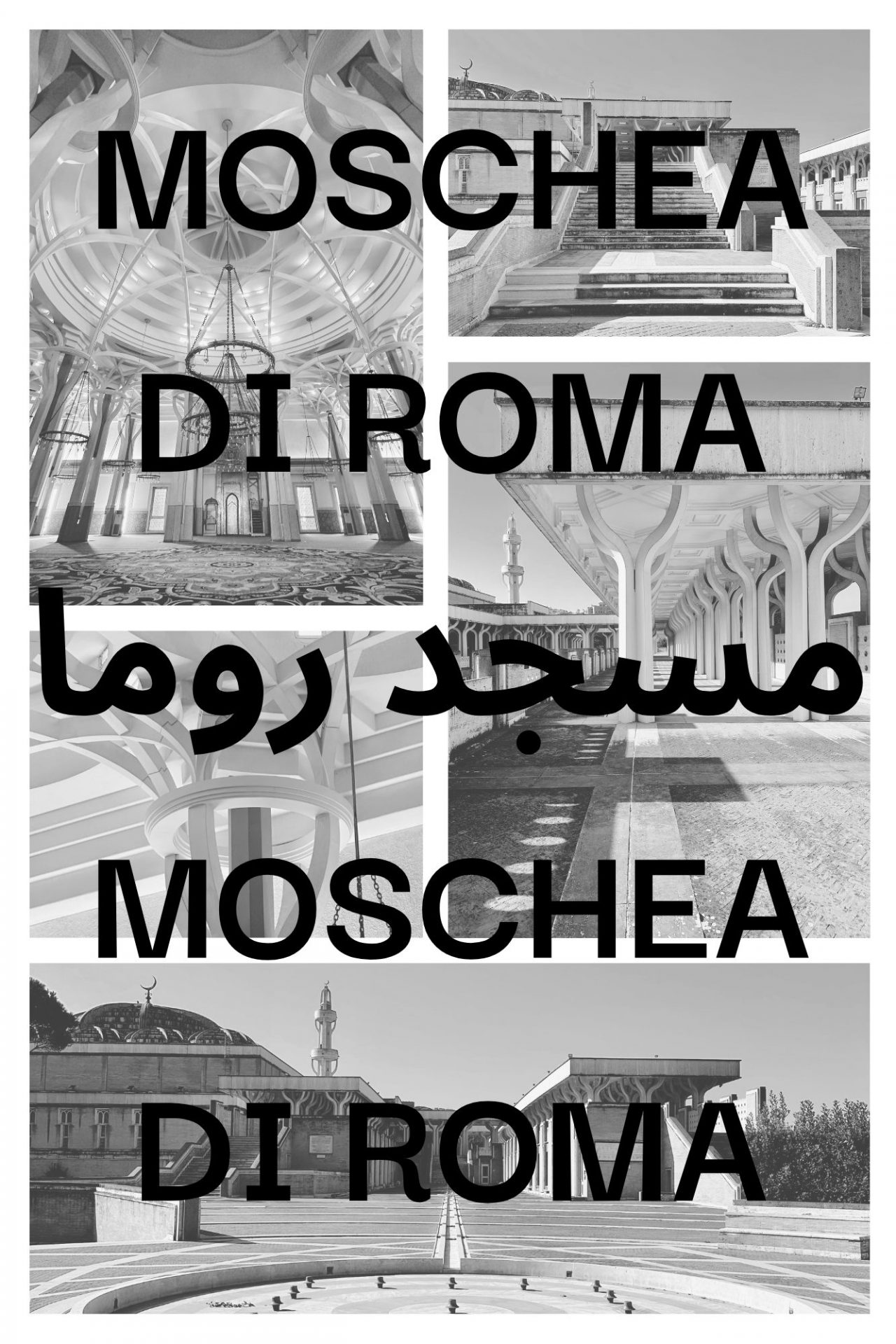

Designed by Italian architect Paolo Portoghesi, in collaboration with British-Iraqi architect Sami Mousawi and Italian engineer Vittorio Gigliotti, the Mosque of Rome is the largest mosque in the Western world. Inaugurated in 1995, the Mosque was built to serve the large influx of Muslims to Rome after the exiled Prince Muhammad Hasan of Afghanistan and his wife, Princess Razia, lobbied for the founding of a mosque in the Italian capital.

In addition to being the largest Islamic temple in the West, the complex also bears the title of ‘Islamic Cultural Centre’ – a name befitting the Mosque’s duality as both mentor (for the Islamic community) and mediator (for the wider non-Islamic community). This is indicative of the building’s diasporic design as the city’s only Islamic temple and one of only eight mosques in Italy.

The role of my research at the BSR is to attribute the fundamental success of the Mosque of Rome to an innate comprehension of the programme, as well as Islam itself. This singular understanding was delivered through British-Iraqi architect Mousawi’s involvement. While Portoghesi has already secured himself a position as a Postmodernist pioneer in the pantheon of architectural heroes, I fear that history will not be as kind to Mousawi.

Following several visits to the Mosque, archives and libraries it has become increasingly evident that Sami Mousawi’s name is passively undermined within architectural history discourse. One example I came across in Italian publisher Alloro Editrice’s 1994 book La Moschea di Roma/ The Mosque of Rome includes an interview with Portoghesi, conducted by Italian architect Mario Pisani, during which he seemingly understates Mousawi’s contribution to the Mosque’s design.

‘Mario Pisani: You had done some research, thus finding yourself in tune with that particular culture.

Paolo Portghesi: I felt in tune with the tradition of the desert. Having visited the tents of the Nomads, I had experienced the emotion of their generous hospitality. I was therefore particularly motivated towards the competition, and I carried it out with enthusiasm. The project contains many elements that are now a reality, while the volumetric scheme comes from Mousawi’s project.’

One should also note that the book not only includes an interview with Portoghesi but also an interview with Gigliotti. An interview with Mousawi is notably absent.

If we compare Portoghesi’s description of events to Mousawi’s – as stated on his own practice’s website – we can see there are a couple of discrepancies to say the least.

‘The Mosque of Rome was the subject of an international competition. Among the 42 submitted schemes, where the design submitted by Sami Mousawi was declared the favourite. The panel of judges finally recommended that Sami Mousawi work in collaboration with Portoghesi and Gigliotti to produce a joint design based on the original design concept of Sami Mousawi.’

Simply because Portoghesi is a more established name in architecture does not mean architectural history should subscribe to the notion that he was the sole genius behind the Mosque’s design, while Mousawi’s contributions are considered merely an afterthought. This prevailing narrative of architectural authorship is symptomatic of the profession’s bias in favour of the concept of the ‘starchitect’.

Born in Baghdad in 1938, Mousawi went on to study architecture in Germany before moving his pre-established practice to Manchester, England. He devoted his life to understanding the Islamic building tradition and championed the establishment, or evolution, of a new identity and language to better integrate the style within contemporary urban fabrics. In light of his untimely passing, I would like to honour Mousawi’s magnum opus and his contribution to architectural history.

As a British-Iraqi historian, researcher and curator specialising in architecture and design, my practice is often an amalgamation of verbal and visual outputs. For my exploration of the Mosque of Rome, I employ poetry, photography, and Indian ink abstractions to interrogate the authorship of – and creative licence afforded to – diasporic Islamic design. My research will culminate in an article for The Architectural Historian where I will delve into the respective roles of co-architects Paolo Portoghesi and Sami Mousawi.

Your research is focused on a modern building in an ancient city. Has your personal experience of Rome’s architectural heritage changed your relationship with the object of your research, perceptions of the building and its context, etc.?

For some, the coexistence of ancient and modern structures encapsulates the dynamic nature of cities, showcasing the continuity and evolution of architectural styles over time. On the other hand, debates surrounding the construction of modern structures, especially those with religious or cultural significance, can reflect broader discussions about identity, inclusivity, and preservation of historical character.

In my experience of the Eternal City, ancient monuments and buildings are treated with respect and reverence; they are something to be seen. Whereas contemporary buildings tend to be somewhat neglected by comparison; they are best unseen. This is perhaps best demonstrated by how many people I have encountered who are unaware of the Mosque’s existence as well as the state of disrepair the Mosque is currently in.

In the court of public opinion, even well-executed modern buildings in Rome fall short in the face of what history deems to be the masterpieces of Roman Antiquity. There is a sense of deep pride for Rome’s ancient monuments because the Roman Empire is perceived as the pinnacle of Italian civilisation throughout history. The question is why? Why aren’t modern buildings treated in the same vein? Contemporary architecture often does not speak to a time when Romans veni, vidi, vici-ed their way around the world but speaks to an increasingly diverse and egalitarian metropolis; therein lies the problem.