An interview with Héloïse Delègue, Abbey Fellow in Painting, in which she speaks about the work she has produced during her residency at the BSR from April–June 2022, ahead of the June Mostra.

The June Mostra opens on Friday 10 June. For more information or to register for the opening night, please see our events page.

You’re currently studying the book Caliban and the witch by Silvia Federici, that retraces the history of the body in the transition to capitalism. Could you explain how this book is linked to your project at the BSR?

The project at the BSR is a continuation of some previous research about the relationships between belief systems, power structures and the disciplining of the body (perceptive, psychic, somatic).

I came across S. Federici’s writings on the ‘struggle against the rebel body’ where she describes how the concepts of body and mind are reminiscent of the medieval conflicts associated with the angels and the beast, the sacred the profane and the duality of high versus low emotions, the head vs the guts…etc. Federici argues that in the 16th century, in Western Europe, bodies became reconstructed as stages of battlefields where opposite elements clash for domination. She says: “In the course of this process, a change occurs in

the metaphorical field, as the philosophical representation of individual psychology borrows images from the body politics of the state, disclosing a landscape inhabited by ‘rulers’ and ‘rebellious subjects, ‘multitudes’ and ‘sedictions’, ‘chains’ and ‘imperious commands.”

In Caliban and the Witch, Federci argues that there was a “need to convert all bodily powers into work powers. The body actually had to die so that labour-power could live”. In fact, she goes further and says that the concept of the body as a receptacle of magical powers was in reality destroyed.

The anatomy of the work I made wants to perform as much psychologically and physically in order to reclaim the concept of the female body as a receptacle for magical powers and source of social insubordination. Something that has been erased before the emergence of capitalist societies. I’m talking about repairing, healing, being empathic, and obtaining what one wants without working, “a conception of a body which did not separate matter and spirit and which imagined the cosmos populated with living organisms and occult forces.”

I believe that performing a form a struggle between mind and body in the making process combined with a very physical and heavy work load is also embodying feminism in the way Rosi Braidotti defines it her recent book Post Human Feminism: “The struggle to empower those who live along multiple axes of inequality. It involves empowering the dispossessed, the impoverished (…) to affirm positively the differences among marginalized people. These differences of material location express different life experiences and also multiple ways of knowing.”

For the June Mostra you’re sewing a huge textile work made by assembling new and old fabrics found in roman markets. Sewing and recycling have always been considered at the core of women’s domestic labour. What’s your experience with them as an artist?

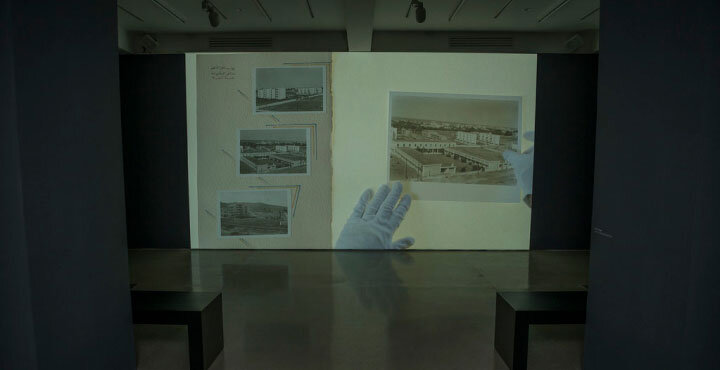

Studio view, work in progress, British School at Rome, May 2022

On my daily walks, I recuperate fabrics, cloth, bed sheets, ‘stuff’ which I then cut and fragment. Some have already travelled around the world a few times; some are worn, destitute, re-owned. Sometimes they lay in large piles of junk. When I first arrived in Rome, I was drawn to some hand made handkerchiefs. Some of them had particular embroidery on them. They look cute, and discarded but they also contain a lot of bodily information, former traces of tears, sweat, snot, dust. That’s how I relate to the material, by imagining the narratives they contain. I want to bring them all together so that a story of a ‘group’ can emerge rather than an individual one.

It’s also about expressing multiplicity of life experiences and knowledge by people who were historically excluded and creating other possible worlds of coexistence.

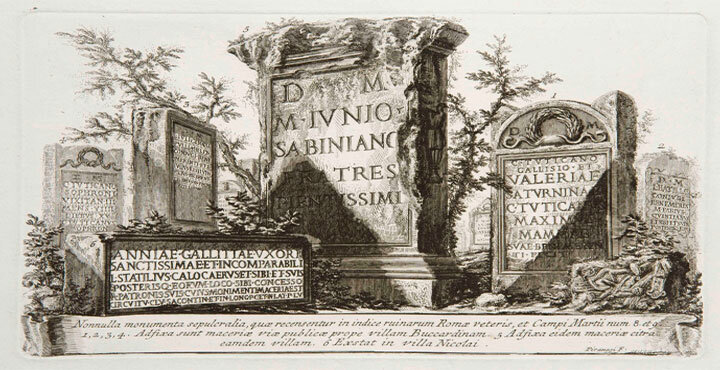

Bringing them into grotesque, monstrous ornamental form is a way for me to draw lightness and humour but also creating objects that embody new power structures. The ornaments perform a variety of functions: ‘It metamorphoses to perform the setting.; it organizes and hierarchies episodes and symbolic elements.(…) Originally, it dehumanizes biblical figures to transmute them into hybrid beings, half men, half animals, half ornaments. They also aggressively underscore the status of the image as an artifice of the imagination and hand.’

By using this as a form, I want to disrupt traditional hierarchical considerations, challenging conventional conceptions of artistic value and merit, whilst firmly positioning itself within the legacies of feminist, post minimal and post conceptual art. I want to be bold in my celebration of the sweet and the silly. With these fabrics, I want to reclaim themes and aesthetic languages that have been routinely devalued, derided and disparaged for centuries by a patriarchal culture that has consistently denigrated the feminine and feminised what is considered ‘superfluous’ or ‘other’.

Left; Villa Farnesina, grotesque ornaments. Right; Sacro Bosco