An interview with Anne McCloy, Ampersand Foundation Fellow, in which she speaks about the work she has produced during her residency at the BSR from March – June 2024, ahead of the Summer Open Studios.

Could you tell us more about the research you are developing during your three-month residency at the British School at Rome?

Reditus In Patria: The Return of the Native (After The Flight of The Earls)

My main interest while in Rome lies in the idea of pilgrimage, relic and the story of the Gaelic Chieftains, O’Neill and O’Donnell, who departed into exile from Ulster in 1607 and journeyed to Rome never to return. In Rome they were granted audience with the Pope and treated as Gaelic royalty. Their tombs are at the high altar in San Pietro in Montorio, a Spanish church associated with the traditional site of the crucifixion of Saint Peter, and marked by the Tempietto, 1502, by Bramante. Known as The Flight of The Earls, this departure is commonly referred to as the end of the Old Gaelic Order in Ireland. Under James I their lands were confiscated and the organised colonisation known as the Plantation of Ulster enacted, the effects of which are still felt today in the partition of Ireland and the aftermath of ‘The Troubles’.

There are three marble tombs in San Pietro in Montorio relating to the Gaels, and inscribed with texts, crests and shields. I have spent many hours in the chapel as ritual, collecting the information from the tombs as relics in paper and wax. This has been a meditative practice, a remembrance, an offering and an honouring of the lives and deaths of these royal Kings of Ulster, whose story features in the collective memory of the Irish psyche. San Pietro in Montorio has become a place of pilgrimage for the Irish in Rome. While working there I have spoken at length with many who come to visit the tombs of O’Neill and O’Donnell, some of whom claim connection through their own family names. My intention is the symbolic return of these relics to Ulster in an act of repatriation and acknowledgement and towards a collective and transformative healing.

Your practice is also concerned with the traditions of fresco and murals as visual narrative tools, and the epigraphic tradition and graffiti. Which parallels do you see between Irish and Roman mythology?

I use the tradition of political muralling in Ireland as a narrative tool in painting. It is interesting to compare this with the art of fresco in Rome conveying both mythological and religious stories. In common is the use of walls as material and illustrative surfaces to communicate ideas. In the same way, the idea of the icon and iconography as devotional, symbolic and enduring can be applied to contemporary political figures and events to sanctify, venerate, mythologise and memorialise their significance in the collective consciousness of the people.

BSR Fellow Eloise Fornieles describes the ‘Talking Statues of Rome’ as ‘vehicles for anonymous expressions of political dissent’. In the context of epigraphic poetry, BSR Fellow Dr Alessandra Tafaro, describes anonymity as ‘a radical political act available to the public’. The anonymity associated with political murals and graffiti underline the radical nature of the art, the artist and the act, and communicates their devotion to a cause, point of view and method of production.

Part of my practice is poetry and performance. Alongside politics and power, poetry is also associated with magic and myth in ancient Ireland. The Ard-Ollamh, the chief poet of Ireland is considered equal to the High King of Ireland. The Lebor Gabála Érenn, a book of mythology complied in the 11th century, tells us that in ‘the islands of the north of the world’ there are four cities to learn the secrets of the druid; knowledge, prophetic art and magical art and where each island is home to a wizard poet.

In the crypt of Santa Maria in Cosmedin church, near to Bocca della Verità, the Mouth of Truth, is what is tentatively identified as part of The Great Altar of Unconquered Hercules (6th century BC) , the earliest cult location of Hercules in Rome. In mythology Hercules is known for his great strength and adventures and parallels can be drawn with the handsome warrior Cú Chulainn, the Hound of Ulster, demigod of Irish mythology and the Ulster cycles. His father is Lúgh who possesses magical tools and is associated with legitimate kingship. Lúgh Is considered the God of Light and Master of All the Arts, and is equated with both Apollo and Mercury.

Rome as Caput Mundi and Holy City has the story of the twins Romulus and Remus as part of its founding mythology. Armagh, the ecclesiastical capital of Ireland and nearby Navan Fort, the royal centre of ancient Ulster, also has a story of twins associated with its mythology. Macha is a sovereignty goddess of ancient Ireland and Ulster and an aspect of the triple goddess Mór Ríoghain, translating from the Irish as Great Queen. Armagh, in Irish, Ard Mhacha, translates as Macha’s height. Navan Fort, in Irish, Eamhain Macha, translates as Macha’s twins.

As a mythological tradition in relation to the Great Altar, established that Hercules visited Rome in his tenth labour when he stole cattle and drove them through Italy, so did Cú Chulainn go to Eamhain Macha to train as a warrior. His deeds are told through the Táin Bó Cúailnge ,The Cattle Raid of Cooley, a central text of the Ulster cycle of mythology.

In another divine and royal connection between Armagh and Rome, Brian Boru, High King of Ireland, died in 1014 and is buried in Armagh Cathedral. His son, King Donough O’Brien, died in Rome in 1064 and is entombed in San Stefano Rotundo.

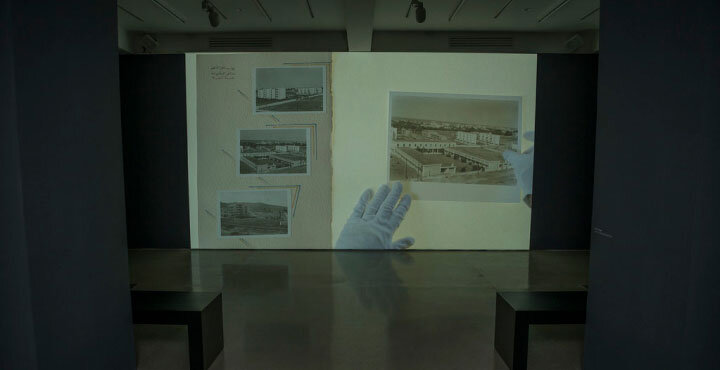

I am interested in ideas around the collective memory and recreation of myth in a contemporary context and how a new narrative based on my current work might be communicated to a new audience. I consider how we collect relics and tell our stories of modern day pilgrimage and trips, photographing ourselves in iconographic locations and with iconographic artworks. The associations discussed previously allow me to integrate stories and imagery from Italy and Ireland towards a new representation. For example referencing frescos and sculptures of Hercules and other deities in the museums alongside the illuminated manuscripts of the Irish monasteries from 6th century and ancient Irish stone carvings, combined with the history of the Irish Kings and my collection of the relics in Roman churches, let me develop a new and integrated visual language. Initially through documenting, photographing, drawing and painting, poetry and performance allow spoken and written word to add a further dimension. The Irish Literary Revival of the 19th century based between London and Dublin, marked a renewed interest in Ireland’s Gaelic heritage which including poetry, music , art and literature, spearheaded by WB Yeats and Lady Gregory. My previous work “Mobilise The Poets’ (2022) was inspired by a call to Ireland’s poets and The Exposition D’Art Irlandais (1922) in Paris that utilised art and culture to launch Ireland as an independent and emerging nation on the world stage. I can apply my creative outputs from my time in Rome at BSR as tools of transformation and healing, towards a retelling, invention or creation myth, and as part of my concept of the Return of the Native : Reditus In Patria (After The Flight of The Earls) and towards the New Gaelic Order (2024).

Further Reading:

FitzPatrick, E. (2017) ‘The Exilic Burial Place of a Gaelic Irish Community at San Pietro in Montorio, Rome.’ Papers of the British School at Rome, 85, pp. 205-239.

Ó Cianán, T. (1607) Turas Na DTaoiseach NUltach as Éirinn: From Ráth Maoláin to Rome : Tadhg Ó Cianán’s Contemporary Narrative of the Journey Into Exile of the Ulster Chieftains and Their Followers, 1607-8 (the So-called ‘flight of the Earls’). Rome : Pontifical Irish College 2007.

King James I, (1607) By the King, A Proclamation touching the Earles of Tyrone and Tyrconnell, London : Barker.

Swords, L. (2007) The Flight of the Earls: A Popular History. Dublin : Columba Press.

Kinsella, T. (2002) The Tain: Translated from the Irish Epic Tain Bo Cuailnge: From the Irish epic Táin Bó Cuailnge. Oxford University Press

Yeats, W.B. (1893, 1902) The Celtic Twilight. London