An interview with Aaron Ford, Sainsbury Scholar, in which he speaks about the work he has produced during his residency at the BSR from September – December 2023, ahead of the Winter Open Studios.

Your project for the BSR suggests that painting can be employed as a reference point along a historical timeline, locating recurrent iconographical symbols and detecting their presence in contemporary visual discourse. What is projected onto the past reveals attitudes towards the present; the historical figures, art and architecture that we encounter arrive loaded with our cultural experience. Could you tell us more?

I see my practice essentially as a search for different symbols which recur throughout art and history. Certain figures, scenes and places have been represented many times over, subsequently making their way into the broader cultural imagination. As I am a painter I use painting as a helpful reference point in locating these moments, both in the past and in contemporary discourse.

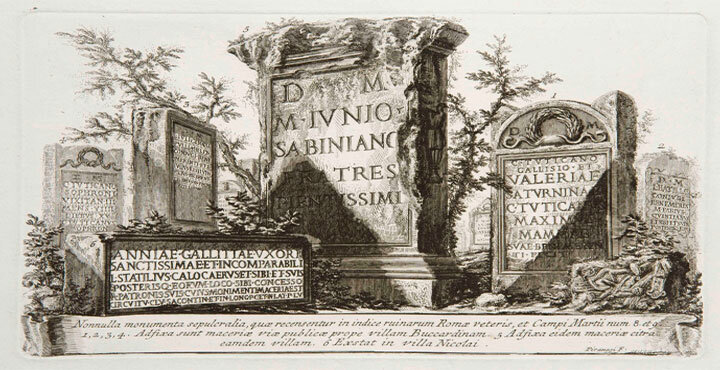

These reference points have previously included, for example, the patterning found on traditional Ghanaian kente cloth. From once serving a specific ceremonial function amongst a group of peoples within Ghana, it now unofficially acts as a clumsy universal signifier for Africa. Another example includes the phrase ‘Ecce Homo’, which today would yield the search result ‘The Monkey Christ’; a botched restoration of a 1930’s fresco in a southern Spanish church undertaken by an elderly parishioner in 2012. In this way a painterly narrative is drawn over 2000 years from early Christian iconography right up to the enthusiastic restorer Cecilia Giménez.

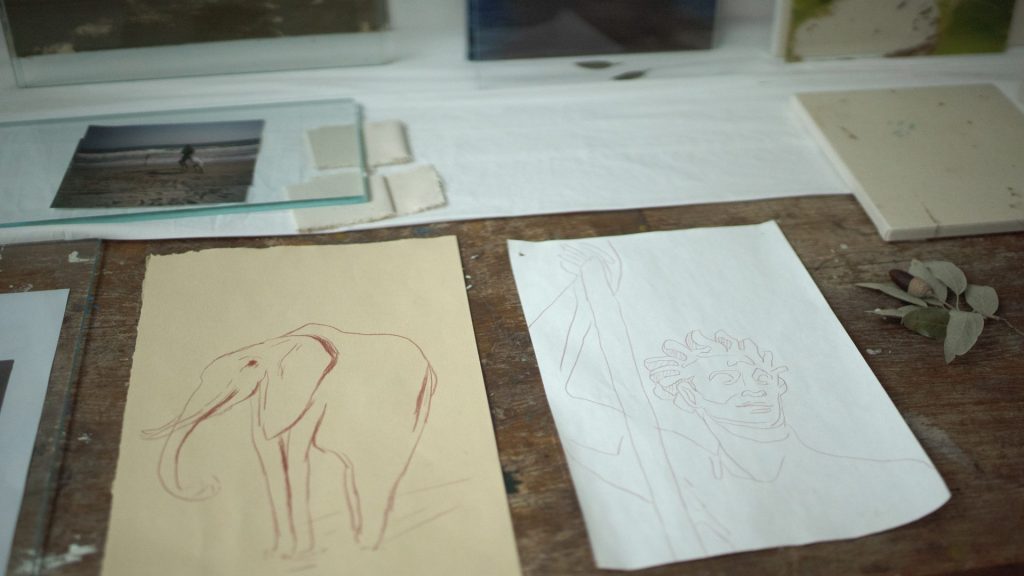

In Rome this has developed into a process of painting on glass. Glass as a surface is multiple things at once. It’s reflective but also allows light through it. It’s incredibly smooth which counterintuitively means that because it lacks the porosity of a material such as canvas, any marks placed on it remain unaltered. Similarly, it can act as a modular vessel for presenting painting as a method of research. I have been continuously rearranging these glass panels in the studio, and in doing so stumbled across a new kind of pictorial ‘trinity’ when discussing the figure of Hannibal Barca, that being the Alps, elephants, and Hannibal himself.

How did you come across Hannibal Barca and how are you developing your study of this figure while in Rome?

Hannibal Barca has interested me for the same reason he interests most people; the Carthaginian military leader acts as a disruption to the narrative which surrounds ancient Rome’s political and military superiority. He is at once vilified and glorified, both in the contemporaneous sources as well as today.

Carthage is located in modern day Tunisia, and although ethnographers hypothesise that Hannibal would resemble North African or Eastern Mediterranean peoples, due to Carthage residing on the continent of Africa he has been reappropriated by black culture as a symbol of black excellence and power. As an artist, this act of projection interests me, and indicates that Hannibal embodies a kind of migrating cultural signifier, primed for the absorption of a multitude of different values and aesthetics.

What I have discovered since being in Rome is the sheer amount of diversity within the cultural groups who lay claim to him. I was made aware through discussion at BSR of a Semitic tradition of identifying with Hannibal asserted by Sigmund Freud on his travels through Rome in ‘Interpretation of Dreams’. Similarly he has undergone an orientalising influence which has subsequently been reabsorbed back into contemporary North African and Middle Eastern discourse. What has been interesting is the continuing awareness that these are not benign figures, the inevitable tensions that arise from continual reappropriation can be sometimes celebratory and sometimes conflicting, existing in a strange liminal space between adoration and notoriety, much like Hannibal Barca himself.