An interview with Maeve Brennan, winner of The Sainsbury Scholar, in which she speaks about the work she has produced during her residency at the BSR from January – March 2023, ahead of the Winter Open Studios.

Your practice resonates around forms of repair and reparative histories and often engages with disciplines that encompass a material practice like archaeology. How do you link subjects that investigate the past with contemporary art practice?

My interest in material practices has led me to work with figures from various disciplines – archaeologists, geologists, conservationists, stone carvers, mechanics. What draws me to these figures is an intimate knowledge of their chosen subject, an embodied knowledge. They form a material understanding of the world through a tangible point of reference.

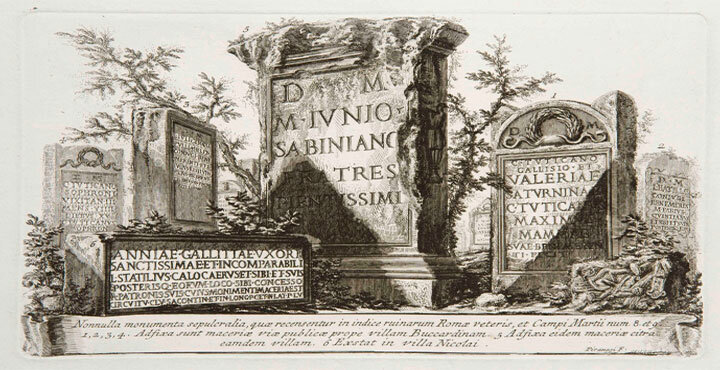

At the core of my practice, there is an investigation of underlying material structures, systems and networks that determine our lived environment. These structures are often unseen, hidden or clandestine. I have been thinking about how the ‘underground’ operates as a thread throughout my practice, both materially as the subterranean (geological strata, archaeological excavations, tombs, mines, sites of extraction) and metaphorically as illicit networks (looting, smuggling and the underground circulation of objects).

My investigations engage with this ‘ground’, excavating layered temporalities and histories to draw out complex narratives across time and place. I am interested in how geology and archaeology – forms of knowledge that interrogate the material past – coincide with and impact our contemporary lived reality. Both disciplines have been exploited to enable forms of extraction that are fundamental to our unsustainable present, in the form of natural resources and the commodification of cultural heritage.

Within the context of this extractive history, forms of repair have been central to my practice. I observe and document processes of restoration and preservation, in cultural heritage sites, scrap yards, museums and archives. This often leads me to ‘backstage’ or unseen spaces – storage rooms, quarries at night, museum basements – and the people that work there. By focusing on these figures and weaving their endeavours back into complex networks of materials and artefacts, I draw out alternate narratives and reparative histories.

Having spent several years in the Middle East – Lebanon and Israel/Palestine – cultural heritage, its circulation, destruction and preservation, have become a particular focus within your work. How are you addressing this focus in Italy?

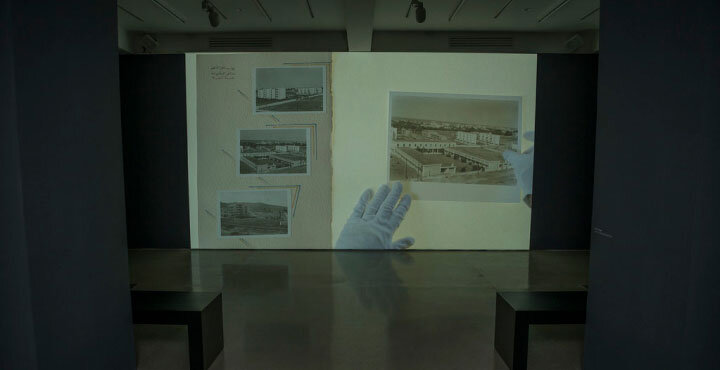

My film The Drift (2017) focused on three figures preserving objects in contemporary Lebanon, mapping converging lines between protected ancient temples, smuggled antiquities and traded car parts. This led me to an interest in subsistence looting as a form of livelihood in ‘source’ countries sustained by a demand in ‘market’ countries. The exodus of cultural heritage through underground trafficking chains can be viewed as a continuation of colonial and imperial extraction. Ariella Azoulay writes of museums: ‘For these institutions to be transformed or reformed, it is essential that looting be acknowledged as their infrastructure.’ Since 2018, I have been developing a body of work titled The Goods which aims to make this infrastructure visible.

Carried out in collaboration with forensic archaeologist Dr Christos Tsirogiannis, The Goods (2018 – present) is a multi-disciplinary project concerned with the international traffic in looted antiquities. Over the years, I have observed and documented Tsirogiannis’ investigations, mapping the illicit antiquities network from looters and smugglers to auction houses and museums. By some estimations, antiquities form the largest trafficking economy after drugs and weapons.

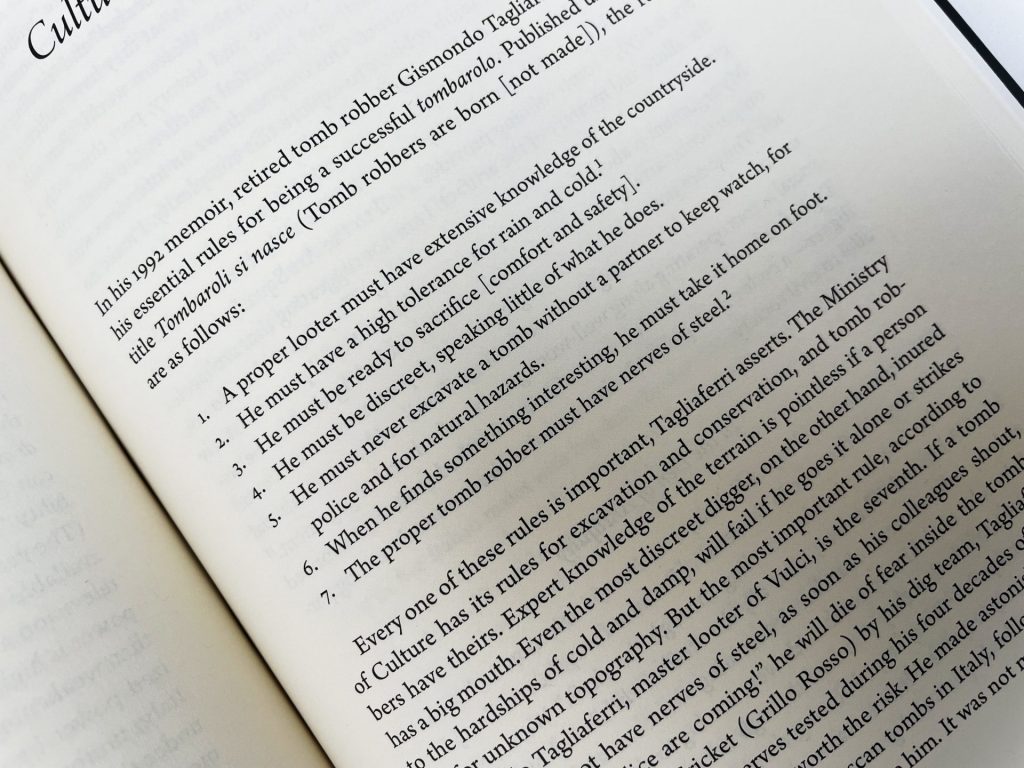

The subject of my latest film, An Excavation (2022), was a series of crates of artefacts looted from southern Italy. Discovered at Geneva Freeport in 2014, the crates belonged to the now disgraced antiquities dealer Robin Symes. Italy has been subject to excessive looting and plays a central role in the trafficking network. Amongst other things, I will be looking more closely at the ‘tombaroli’ (tomb-robbers) and the role of local knowledge in this illicit network. I will visit known and potential looting sites and engage in fieldwork and interviews – gathering stories and anecdotal evidence to build a picture of this underground economy.