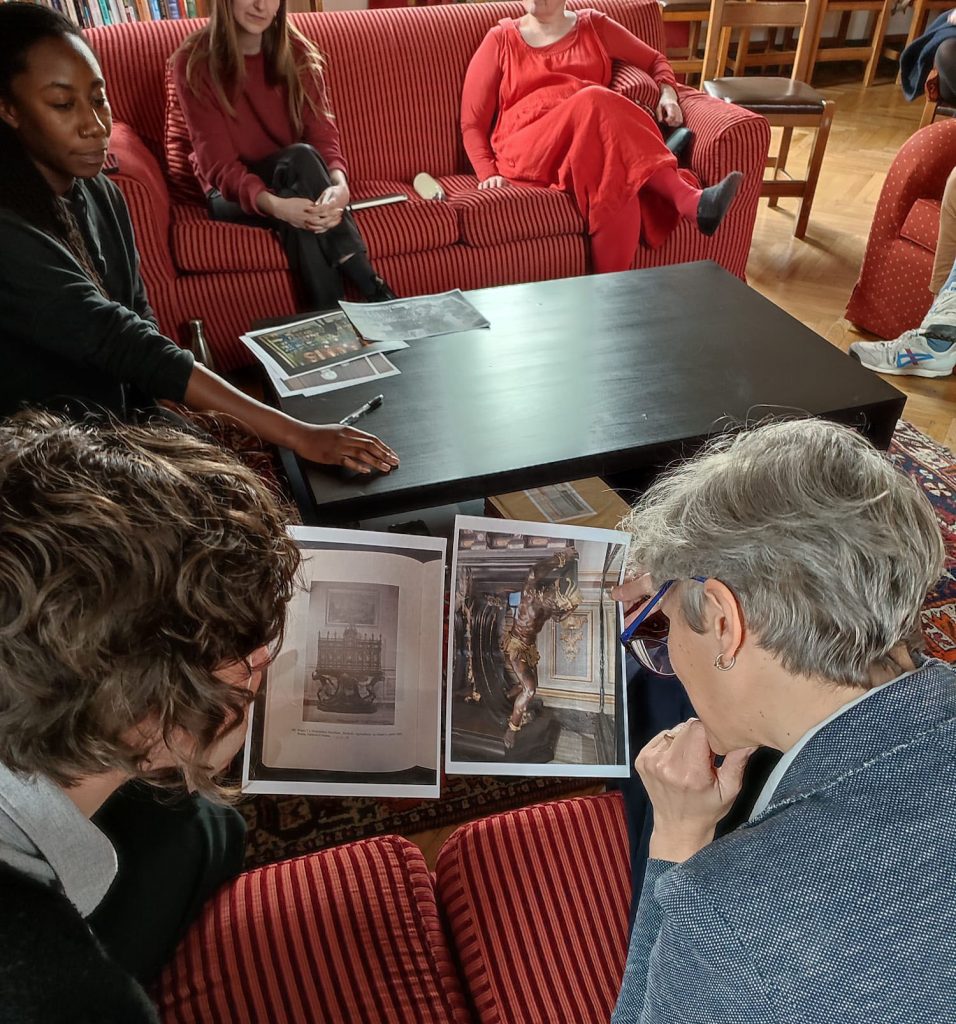

An interview with Holly Graham, winner of The Sainsbury Scholar, in which she speaks about the work she has produced during her residency at the BSR from January – March 2023, ahead of the Winter Open Studios.

You’re a cross-disciplinary artist, working predominantly with print, audio, photographic images, text, and moving image, often in response to archive and museum collections. Much of your work looks at ways memory, narrative and fictions shape collective histories. Could you tell us more?

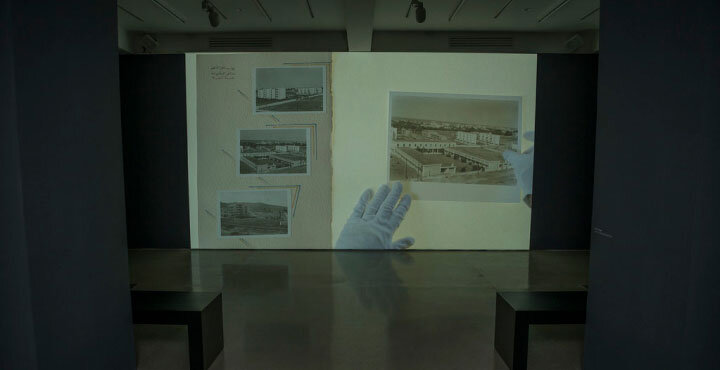

Yes, so I often find it quite hard to describe what I do when people ask, because as an artist I don’t really have a particularly strong commitment to any one medium or methodology. What I make and the form it takes is really dependant on the specific project. But I often return to the fact that my background is rooted in printmaking – the course I specialised in for my MA. While I work in quite a multidisciplinary way, I think I often using the lens of print as a discipline as a starting point – print in terms of thinking about reproduction, dissemination, duplication, repetition, traces, material degradation, memory. I work a lot with collections of existing material, and I guess the interest in the archive and the museum is grounded in thinking about how we collectively choose to document things, and what we societally deem worthy of recording or holding onto. And then I’m interested in how these records are collected, in the practices of collecting, how they’re grouped and stored, curated and accessed; often to tell potentially selective narratives.

I’m interested in looking at these collections and considering alternative ways of positioning material, in order to highlight or illuminate other possible strands of story-telling – in attempt to try to amplify quieter or omitted histories, marginal histories. I’m interested in multifaceted, or layered narrative, and the inclusion of multiple voices. Oral histories have been central to much of my work previously as a sort of ground-up, more democratic way of recording or gathering a sense of collective pasts. And lots of the work I make is often specific to sites or particular localised histories; but also very much inevitably has my own subjectivity embedded in it – as a woman, as a diasporic black person, as a cultural practitioner, etc.

An ongoing strand of research within your practice, instigated in 2018, takes as its starting point a pair of mid-18th century ‘blackamoor’ Meissen porcelain sweetmeat bowls, in the V&A Museum collection to consider histories and legacies of European colonialism. Replicated across Europe throughout the nineteenth- and twentieth-centuries in variations of delicate porcelain and clumsy earthenware these figurines form part of a wider design history of ‘blackamoor’ sculptures embedded into architecture and furniture, particularly prevalent in northern Italy from the early 1600s. Are you continuing this research in Italy?

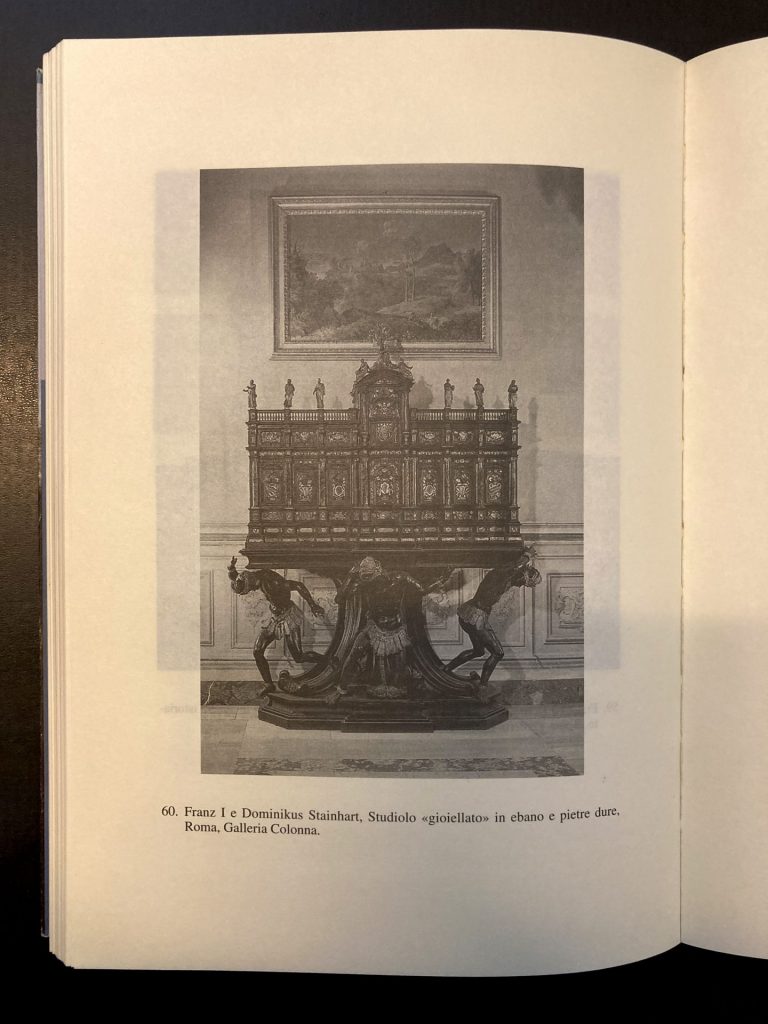

I am yes. My proposal for the BSR is in response to this body of work, and looks to further interrogate the development of this motif of the ‘blackamoor’; with a focus on Baroque furniture design. This trend of blackamoor figures was particularly prevalent in 17th and 18th century Venice and Florence, but are present in Rome too; carved from exotic woods, painted and gilded, and often positioned in functional gestures of servitude – kneeling or bent double to support a cabinet or table top, standing to attention holding a cushion or tray to receive the gloves of visitors, holding aloft lamps, or sprouting candle fixings and vases from their turbaned heads.

I’m interested in what’s come before too, which might have helped shape the development of the motif – representations in Italy from antiquity, through to the Renaissance, to consider how these formations of representations of the racialised ‘other’ have unfolded and shifted over time. And I’m also interested in looking at other artisanal motifs of conquest, capture, subjugation and enslavement more broadly. So all in all the scope of research is really expansive and I’m having to sort of zoom in and out repeatedly in my attempts to make sense of it all.

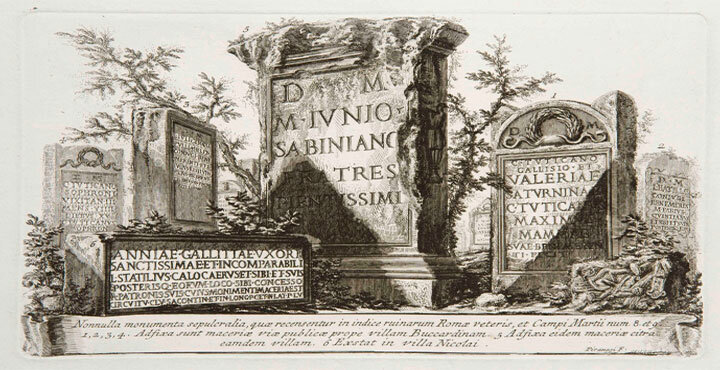

I’ve been looking at the ‘négrillon’ motif – 1st and 2nd century stone carvings of young black boys in positions of servitude. There are lots of examples written about young bathing attendants in particular; who would have been present in Roman society as living beings as well as rendered in stone. One such example is held by the Vatican Museums in the Galleria dei Candelabri. These representations would often be a little smaller than life-size, showcasing a relationship of power and domination verses submission and servitude between bather and attendant.

The racial dynamics governing the social norms of the time would have been very different to how we understand them today, with the context of modern European colonialism and of the transatlantic slave trade, which really engrained racial categories of Whiteness and Blackness.

But here categories of foreigner and enslaved labourer also come into play. Another award-holder here, a numismatist, kindly pointed me in the direction of the captive figure in coin designs from the 1st and 2nd century AD, often found kneeling and holding the victor’s trophy or in some cases the victor himself. These kneeling figures in supportive roles are also often depicted in at diminutive scales, again reinforcing logics of status and power.

In Greek mythology, the god Atlas was forced to shoulder the weight of the heavens as condemnation for military defeat. I’ve been looking at caryatids and atlas figures, which play supportive structural roles in holding up architectural space, standing in for columns. And I’ve also been thinking about the idea of petrification as a punitive measure – punishment through being made inert in stone. And I guess the position that you are captured in – quite literally encapsulated in – is very much part of that. I’ve been thinking about gesture – of servitude, of support, of holding, of carrying, of burden, of haptic tension, and of potential resistance, of push-back.

But I know very little about many of these things that I’m touching on. Lots of the contexts I’m looking at are entirely new to me, an outside of my area of expertise – as primarily a maker of sorts, as opposed to a historian or classicist. I currently feel very much in a stage of absorption and gathering. I’ve been looking at things, making visits, reading. I’m feeling fairly overwhelmed by the vast amount of stuff there is to look at and take in, and I don’t feel ready to make anything at all really much as yet. The blackamoor objects feel like quite difficult, complex and weighty things to hold and navigate, so I’m allowing myself for the time-being to sit with that discomfort and see where it takes me.