Trigger warning for racism and white supremacy.

An interview with Hardeep Dhindsa, winner of Leverhulme Study Abroad Scholarship, in which he speaks about the work he has produced during his residency at the BSR from January – March 2023, ahead of the Winter Open Studios.

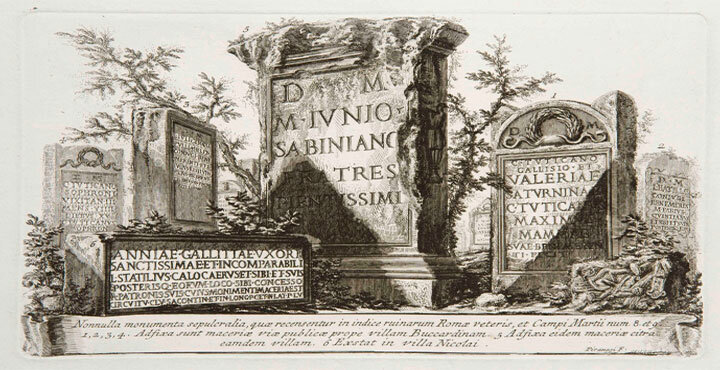

You’re developing your doctoral project at the BSR with a Leverhulme Study Abroad Scholarship in Humanities and your research in Rome is titled White British identity on the Grand Tour and the inheritance of a classical past, 1756– 1815. In life you’re also a digital illustrator whose practice focuses on the use of colour to critique the myth of Whiteness in classical sculpture. Could you explain what the myth of Whiteness is and how your research at the BSR is intertwined with your artistic practice?

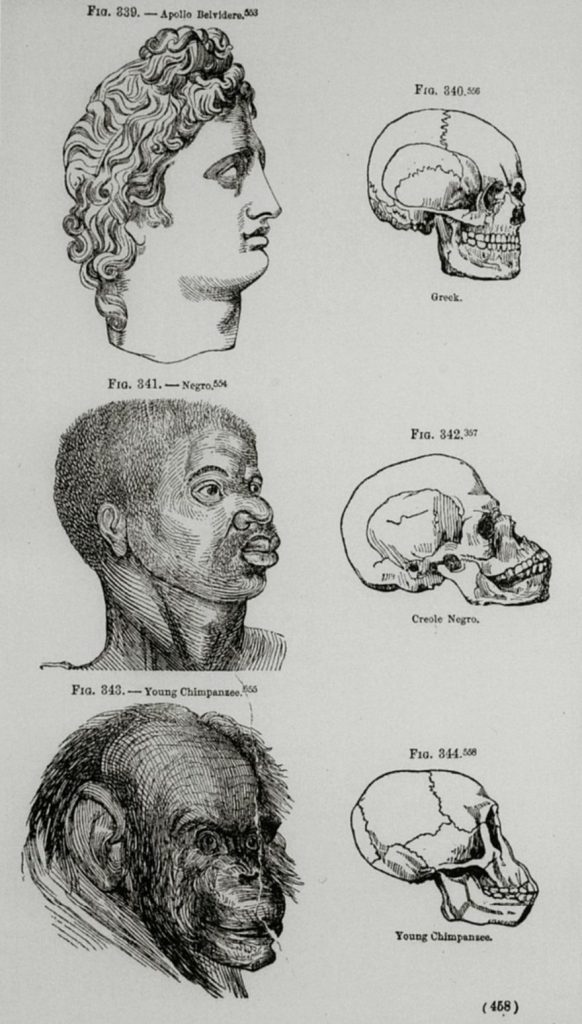

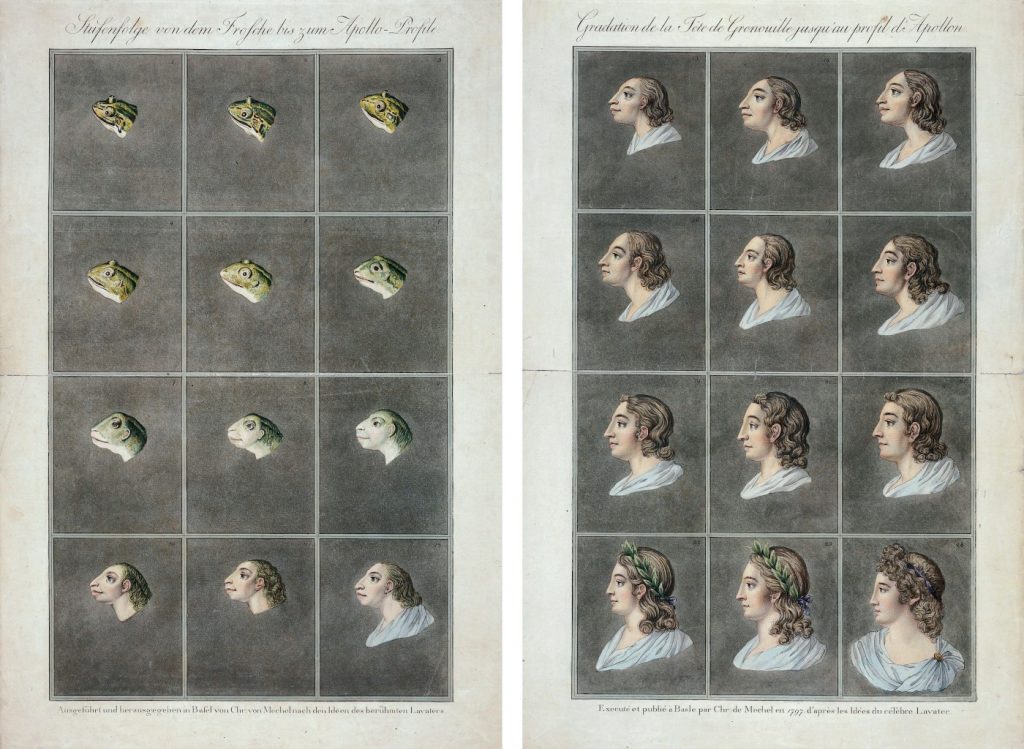

In general terms, the myth of Whiteness in classical sculpture is the false visual identity that has defined classical sculpture since the Italian Renaissance. For the West, these sculptures are synonymous with whiteness and to restore them to their original polychromatic state means to deny white identity one of its primary foundational origin myths. There is no shortage of artists over the last 500 years who actively support this whitewashing: Winckelmann believed ‘the whiter the body is, the more beautiful it is.’; Rodin is rumoured to have said ‘I feel it here [my chest] that they were never colored.’; Le Corbusier wrote ‘Enough. Such stuff founders in a narcotic haze. Let’s have done with it…It is time to crusade for whiteness and Diogenes.’ Blumenbach included ‘the inhabitants of the world known to the old Greeks and Romans’ under ‘Die Caucasiche Rasse’.

My doctoral work exposes this deep-rooted connection between whiteness and Classics, and my artistic practice is an extension of that work. The material I look at is visual in nature – Whiteness in my thesis is as much about the physical presence of whiteness as it about its cultural and political potential. Art, then, is a way for me to communicate my work visually in a way that my words cannot describe. I am also sensitive to the inaccessibility of academia and its power structures. I conduct my research in a way that engages with an audience outside of academia and my art is part of that.

According to your project how would the ancients perceive white marble sculptures in museums?

Probably with words too rude to put in this blog post. I discussed the problematic nature of white marble in the above answer, so this time I’ll focus on polychromy and discuss the evidence we have of ancient colouring. I will say that my immediate doctoral research does not cover polychromy since I work to decentralize Whiteness, but my work is still heavily influenced by the work that is being done by scholars like Vinzenz Brinckmann and Jan Stubbe Østergaard. Unfortunately, it is not enough to state the simple fact that these sculptures were not white, since classical imagery such too strong a hold on contemporary Western (White) visual identity politics. But there is no shortage of ancient evidence. In his Quaestiones Romanae 287d, Plutarch mentions coloured statues in a passing comment: ‘The polishing [γάνωσις] of the statue was necessary: for the red ochre [τὸ μίλτινον] that they used to colour ancient statues soon fades.’ Pliny the Elder also attests to this when he writes Praxiteles’ response to being asked about his favourite work: ‘The ones to which Nicias [the painter] has set his hand’ (Natural History XXXV). Texts are not, however, the most explicit evidence of ancient polychromy. Countless statues themselves hold traces of their pigments – the Augustus of Prima Porta, now in its white haven in Palazzo Massimo, held onto its colour when it was excavated, as did the objects unearthed on the Athenian Acropolis in the late nineteenth century. Even after the attempts to physically hide these traces – forcing leftover pigments into the nostrils’ of the statues, botched restoration jobs, exhibiting them in poor lighting – evidence remains on our side, and hopefully that means one day the ancients might actually recognise their art.