An interview with Maeve Brennan, Sainsbury Scholar, in which she speaks about the work she has produced during her residency at the BSR from April – June 2023, ahead of the Summer Open Studios.

Recently you went on a trip to Puglia to continue your project about traded archaeological artifacts. What did you have the chance to see and how is this trip informing your research?

The subject of my latest film An Excavation (2022) was a series of looted vases discovered at Geneva Freeport in 2014, in a warehouse belonging to notorious antiquities dealer Robin Symes. Together with archaeologist Vinnie Norskov and her colleague Mary-Helene Van de Ven, we travelled around Puglia, tracing the potential looting sites for these vases, visiting a number of locations where ancient Apulian cities once stood – Arpi, Siponto, Salapia, Canosa, Ascoli Satriano.

I wanted to see and document these landscapes, thinking at once about the buried histories beneath the surface and the illicit excavations that continue into the present day. Arpi was one of the most significant ancient cities in Italy with many aristocratic families whose tombs populate the fields close to contemporary Foggia, providing substantial resources for looters over the decades. We visited the Medusa tomb, looted twice before it underwent a rescue excavation, the results of which are on display at the Museo Civico in Foggia. We were told that the tomb was discovered because a tombarolo (tomb-robber) was intercepted with artefacts stolen from the site.

When visiting these looting sites, we encountered verdant fields filled with spring flowers and wheat crops. The dominance of agriculture and monoculture farming was clear, with abandoned industrial ruins scarring the landscape. The material we gathered will form the basis of a film on ‘looted landscapes’. Taking the form of a landscape film, it will draw out the rich histories that populate this region and how these intersect with contemporary land use – by farmers, archaeologists and, in particular, unauthorised excavators. My interest in the tombaroli stems from their knowledge of the land and what is beneath the surface. Fiona Greenland (sociologist and author of Ruling Culture) states that a tomb robber requires ‘an exquisite sense perception of undulations in the landscape and changes in soil quality, and a penetrating “vision” into the soil that can be learned only through years of living and digging in a particular field or valley or hilltop’. This form of knowledge disrupts dominant structures, it sits outside of the formal discipline of archaeology and operates outside of state law (in fact, it precedes both). This research builds on my interest in alternate histories, often engaging with oral testimonies that complicate dominant narratives, particularly through forms of embodied knowledge and ties to place. This project is ongoing and Vinnie Norskov and I have plans to return next spring to continue with fieldwork and filming.

After six months in Rome your scholarship is coming to an end. How do you intend to develop the projects started in Italy back in the UK?

I came to Rome to continue with my ongoing body of work The Goods (2018–present), investigating the illicit antiquities trade. Being in Italy has facilitated so many encounters and connections and they feel like the starting point of a much longer engagement. I was lucky enough to meet with renowned forensic archaeologists Dr Daniela Rizzo and Maurizio Pellegrini, both colleagues of my long-term collaborator Dr Christos Tsirogiannis. Rizzo and Pellegrini shared their stories with me from over the decades. Their work has been key in exposing antiquities trafficking networks and instigating the repatriation of numerous significant objects to Italy, as well as building the case against now-convicted dealer Giacomo Medici.

I have visited the remarkable Etruscan cemeteries at Tarquinia and Cerveteri, both subject to significant looting over the years. It was incredible to see the well-preserved tomb structures (dating back to the 9th century BC) at Cerveteri and how they are integrated into the surrounding landscape. At the local museum, I was able to visit the Euphronios krater, an object I have read about for years. Looted in 1971 and bought by the Met for a record-breaking $1.2 million in 1972, this vase and the story of its repatriation in 2008 is central to explorations of the illicit antiquities trade. Considered to be one of the finest examples of Ancient Greek vases in existence, it depicts the death of Sarpendon, attended to by Sleep (Hypnos) and Death (Thanatos), as Hermes looks on. I have sought out significant objects of this kind at various museums, including the Apollo mask at Palazzo Massimo, famously discovered by the tombarolo Pietro Casasanta and the Polychrome griffins in Ascoli Satriano, returned by the Getty Museum in 2007. It will take time to process all of these rich encounters but they will contribute to my long-term research project The Goods in various forms, and also towards a feature film that I am developing.

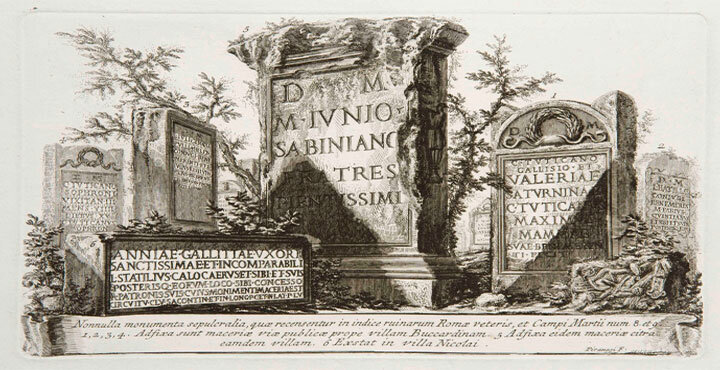

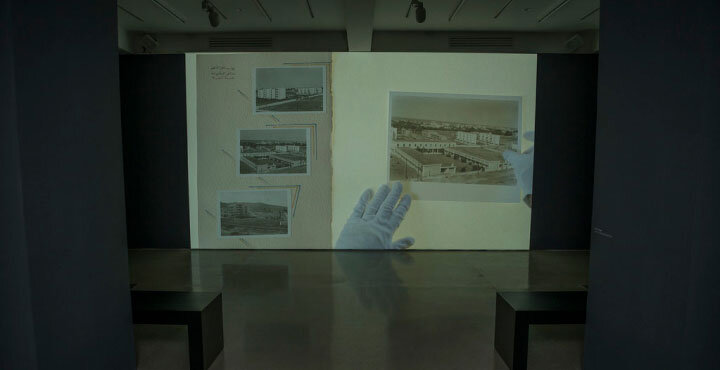

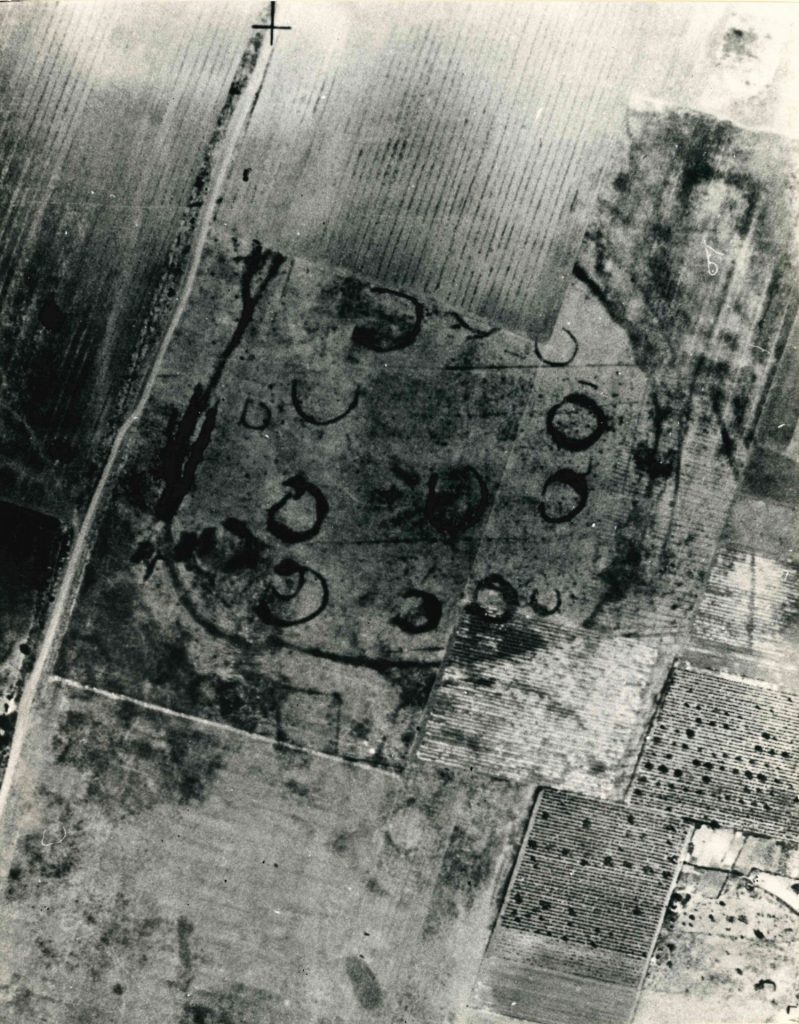

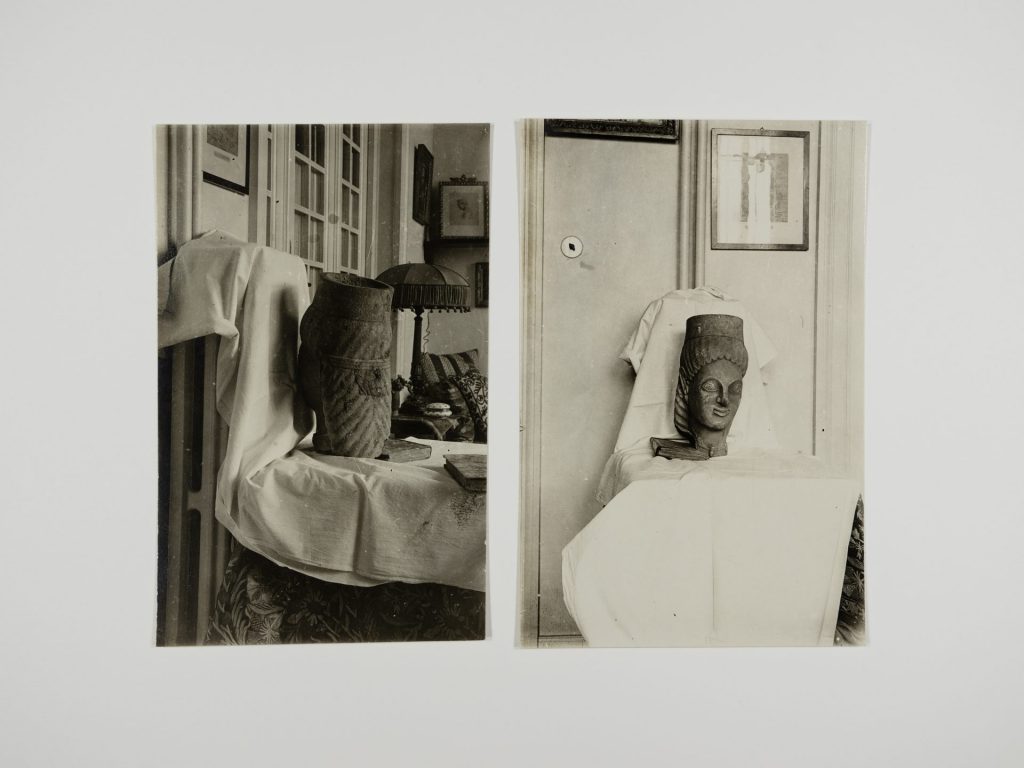

Beyond this main focus, my time in Rome has opened up numerous lines of enquiry. I have worked closely with various archives held at the British School at Rome, all in some way addressing concealed histories. The aerial photographs of John Bradford, taken in the years 1943–1945 from military airplanes over Puglia, depict remarkable images of buried landscapes. Ancient structures appear as defined lines in the agricultural land ‘enabling sense to be made out of what from the ground, might appear to be individual, unconnected marks’. John Marshall’s archive of photographed artefacts presented to the Met for sale has also been generative. I am particularly interested in images where the objects are presented out of context, in living rooms, propped on books or placed in front of provisional staging. We rarely see these objects in such contexts, in states of transition, and these images unwittingly reveal the backstage of the market of such goods. I have been experimenting with these images in various ways and will continue to collaborate with the BSR and the wonderful archivists there in developing a series of works.

This period of research has also seen a continuation of my interest in stone, its historical and cultural significance, its extraction and its circulation (initially explored in my film Jerusalem Pink, 2015). I discovered the somewhat hidden BSR marble collection back in January and have been thinking with these materials during my time here. These marbles are from Imperial Rome, sourced from various quarries around the empire – sitting somewhere between geology and archaeology. It has been a rare pleasure to have these materials physically in my studio where I have been experimenting with them in various ways (photography, film, scans, prints). Time has been a central subject within my work over the last decade, in the form of layered histories that I excavate through my filmmaking process. Here, I am thinking about time as a material, with new works made from stone and paper.