An interview with Holly Graham, Sainsbury Scholar, in which she speaks about the work she has produced during her residency at the BSR from April – June 2023, ahead of the Summer Open Studios.

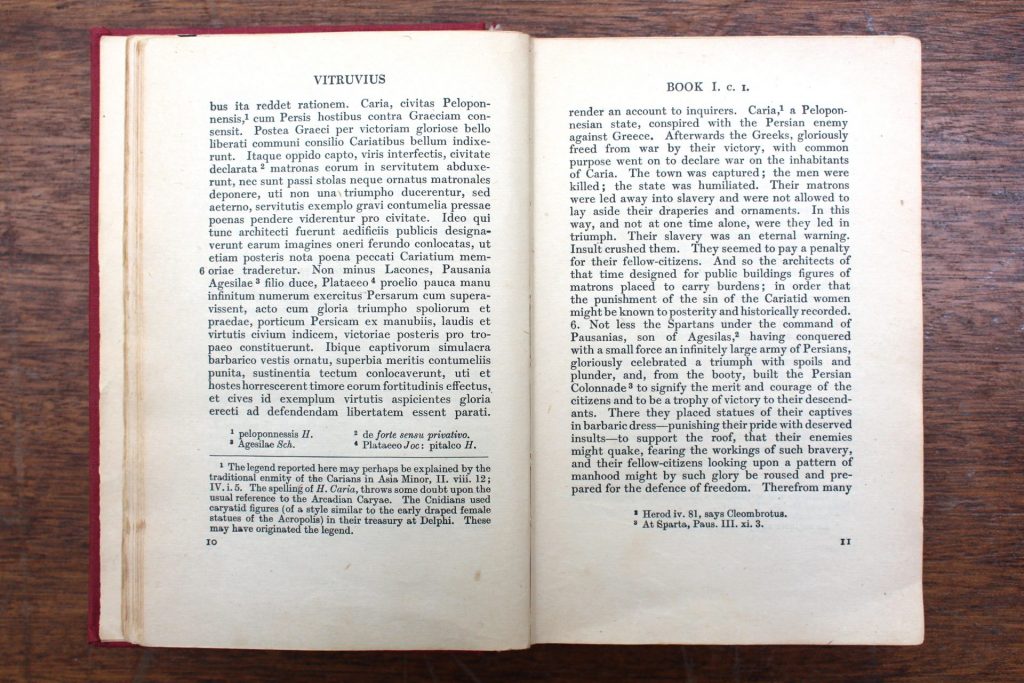

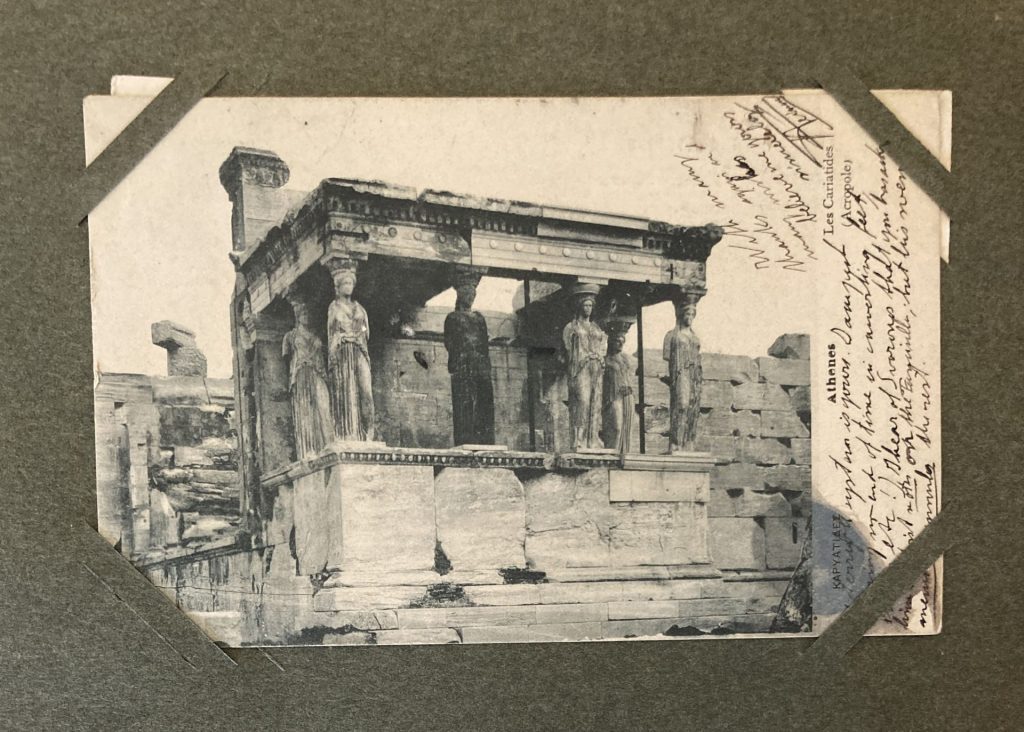

Your work for group exhibition ‘On the meaning of Gossip’ takes as its starting point an extract from Roman architect Vitruvius’ seminal text ‘De Architectura’, written in the 1st century BC. In the excerpt, the writer proposes an origin story for the architectural motif that sees female figures standing in for columns to uphold roofs of temples and monuments. How are you developing this topic?

This strand of research stems from my research around motif of the blackamoor in Baroque Italian 17th and 18th century furniture design. I was interested in the load-bearing, holding gestures often taken up by these figures, in some cases standing in for the base of a table, or acting as a lampstand holding a candelabra, or bearing a tray for gloves or trinkets to be deposited on. I’m interested in how the imagery has developed, so I’ve been thinking about gestures of load-bearing more broadly, and that’s where the caryatids come in.

In terms of the show, it was also a case of thinking about the framing of the exhibition, and wanting to draw out a strand of the research that spoke to that focus. The title of the exhibition is ‘On the meaning of Gossip’ and is rooted in Silvia Federici’s essay of the same title. Marta Pellerini, who was curating the show, shared the essay with all of the artists involved, and we all read it and fed back our thoughts; thinking about points of connection between our work and elements touched upon in the text. We talked about gossip as a ground-up non-institutional form of memory-building and of growing collective histories.

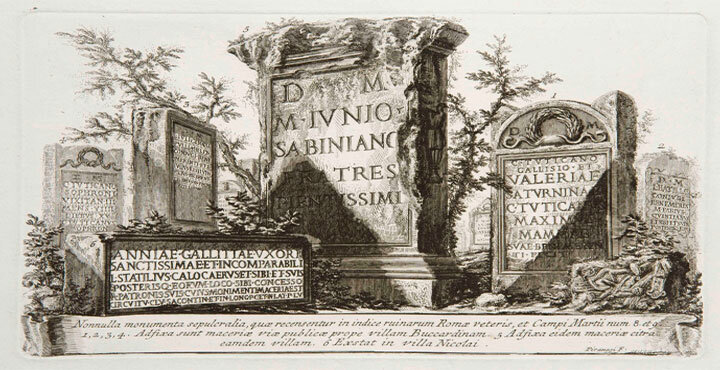

I was struck by the overlaps in forms of oppression and resistance outlined in the essay – spanning protestors to enclosure of the commons, women, and enslaved people. In the essay, Federici touches on an instrument of torture – the ‘___’, which would be used to silence and humiliate, clamped over a subject’s head, and mouth, locking the tongue in place, preventing speech and communication that might have been resistant to more dominant forms. I’m really interested in this idea of silencing and punishment here, and began thinking about what forms silencing can take more broadly; thinking about the idea of ‘speaking for’ and ‘speaking over’ in relation to representations of ‘others’. I also started thinking about petrification, rendering inert in stone, as a form of silencing. So in my work for the show, I wanted to think about these idea of punishment and silencing for the caryatid women and the defeated Persians which take the form of atlantes, spoken of by Vitruvius; and to read this across to the blackamoors too with the weights they are also made to carry in their static, sculpted forms.

But I also wanted to think about that double-edge of the word ‘gossip’, with its current meaning as one that conjures slippery narratives, half-truths, and fictions, distorted retellings. I wanted to think about this in relation to languages of visual representation. Although Vitruvius’ reading of the caryatid forms as inherently punitive has been questioned, his influence has regardless shaped subsequent thinking and design, suturing the motif and ideas of punishment together. Similarly, the blackamoors embody a litany of conflated bundled identities and signifiers, but all in all they become shorthand for a subservient ‘other’.

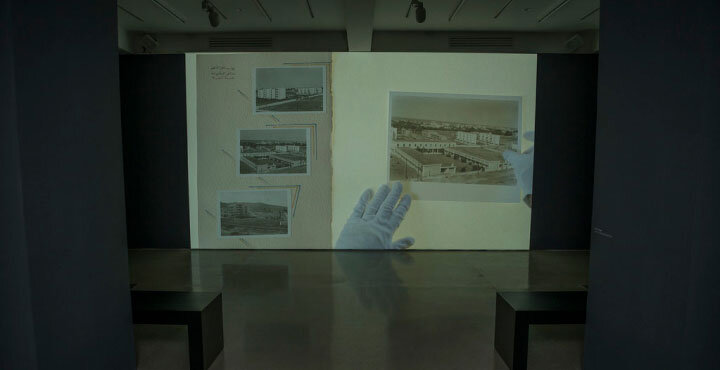

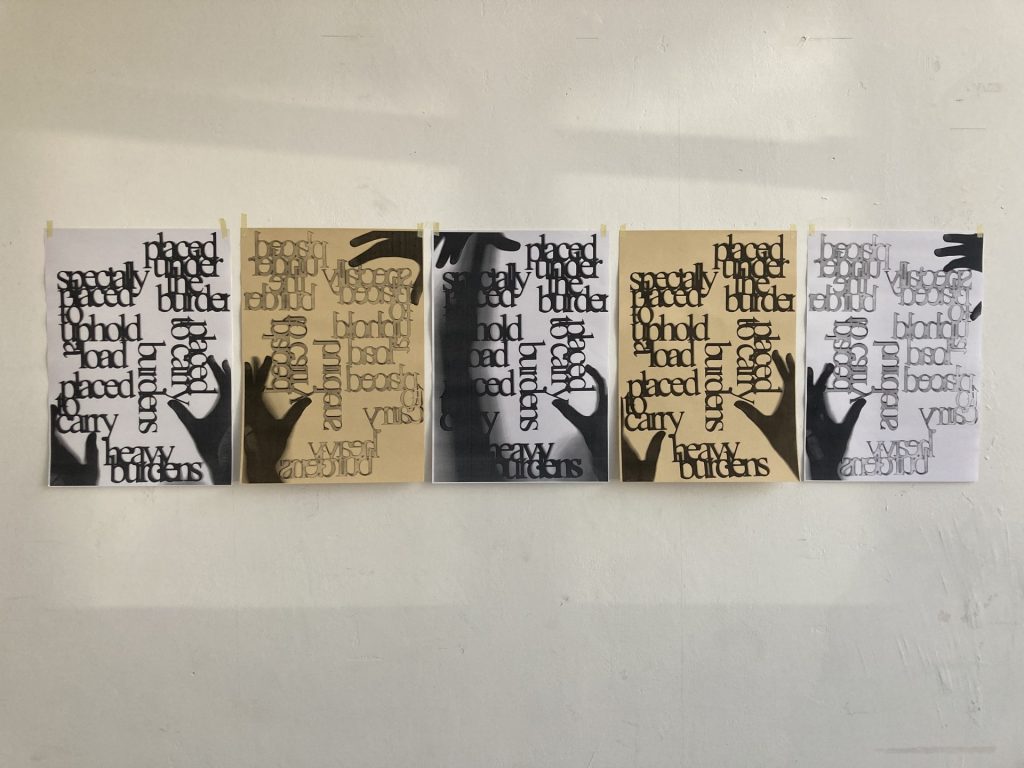

Thinking around gossip, language, and interpretation; I felt like text and translation could be a useful grounding point for the work. So that’s what it became. The work takes the form of excerpts of a poem of sorts, constructed from fragmented extracts of Vitruvius’ text that speak of load-bearing and burden-holding – with the variations translated by classics scholars & Google translate. The text is part of a wider writing practice I’ve been trying to cultivate here, and that’s something I hope to develop further. Currently I have a working document, which is very fragmented, but I recently was invited to contribute to an event artist Sophie Jung programmed at the Swiss Institute, under the spectacular title ‘Dropping the Canon / Drooping the Cannons’ that provided a good motivation for drawing some parts out and together. The event invited several speakers and readers to think around the idea of ‘the canon’ or ‘canons’, and it felt really relevant to much of my thinking about the authority of imagery – of trope, motif and style. It’s something that I’ll continue to think and work through.

Recently you met Doc. Patrizia Piergiovanni, Director of Palazzo Colonna in Rome who showed you two peculiar cabinets belonging to the aristocratic Colonna family. Could you share with us what was their function? Do they have a (different) function today as well?

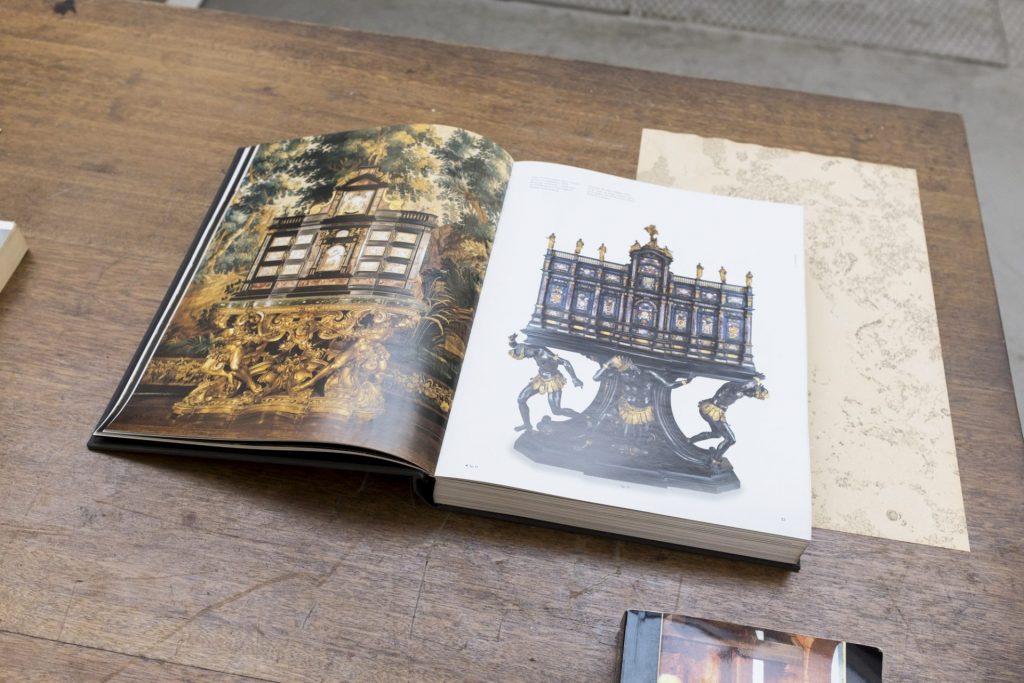

Yes, the cabinet – or ‘studiolo’ – was quite a common piece of Baroque furniture. It was a structure that would contain various compartments, to hold objects, papers and documents for safekeeping; a sort of very ostentatious vault, safe, or storage unit. While they carry this functional purpose, they seem to have really been predominantly used for purposes of display and power, located in public-facing areas of villas and palazzos. The materials employed tend to be incredibly luxurious.

The Palazzo Colonna cabinets were commissioned by Lorenzo Onofrio Colonna, and produced by Dutch born brothers Dominicus and Franz Stainhart in their workshop in Rome in the 1670’s. They are constructed from ebony and sandalwood, carved and polished, and inlaid with ivory, gold, and semi-precious stones illuminated with silver backing. The two cabinets are similar in scale and sit at either end of a room at the entrance to the impressive Sala Grande. Today, they’re also behind glass, as if to hammer this function of display home. While these pieces open up, apparently in their contemporary lives at Palazzo Colonna they only ever have opened for restorative work to take place.

What makes the Palazzo Colonna different from other similar counters I’ve encountered is the ‘mori’ who support the structures from below. The figures are described as ‘mori’ – the Italian word translation of the word ‘moor’ but also of ‘blackamoor’ – in the account books at the time they were being made, in spite of being intended to represent vanquished Ottomans following their defeat at in the 1571 Battle of Lepanto. Here again there’s a function of holding, but the main purpose of the mori is again this display of wealth, power, and victory. And it’s also the beginning of a real othering. The more you look around the Sala Grande, the more you see. They’re everywhere. Troops from both sides engage in battle on the frescoed ceiling, while sculpted enchained Ottoman’s flank the upper corners of room, and gilded mori lie below at ground level, slumped against supports for marble-topped tables. Art historian Christina Strunck calls the representation of the Ottomans on the ceiling ‘the noble enemy’, at odds perhaps with some of the more derogatory representations embedded into the furniture and architecture of the space; but argues that even these more ennobled depictions were intended only to serve to make the Europeans look even more impressive for this triumph over such a well-matched enemy. I tend to think that objects often tell you much more about the maker than about the subject depicted, and this certainly feels to be the case with these objects. It feels strange for these pieces to live on in a house that is still in part lived in by today’s generation of Colonna family members.

I recently came across an article as part of an auction house listing for an 18th century north Italian blackamoor tabouret (or small table) that attributed the Stainhart brothers with creating the earliest mori, so there’s definitely a lineage there. While these earlier models spared no expense, employing rare and exotic materials; later objects would emulate these luxurious surfaces through mimicry and clever craftsmanship, darkening wood to make it look like ebony and in turn like the blackest of black skin for example, and painting wooden bases to resemble marble plinths. In the work for ‘On the meaning of Gossip’, I wanted to draw parallels between the punitive holding gestures referred to in the Vitruvius text, and the blackamoor motif, so within the work I developed the materials aim to reference the craft, layering, surface, and fakery embedded in many of the blackamoor sculptures. The text is made of hard-wood veneered plywood, which I’ve then ebonised with home-brewed iron acetate (a traditional potion of steel wood – or in the past rusty nails – dissolved in white vinegar). I’ve also been working with oriented strand board, and I like the idea of this alongside plywood as a cheap composite material, that embodies possibility for surfaces of visual trickery while layering and binding together an amalgam of stuff from different sources. It feels somehow analogous to the combined points of reference an influence, conflated identities, and projections of represented selves and ‘others’ bound up in the blackamoor motif.