An interview with Hardeep Dhindsa, Leverhulme Study Abroad Scholar, in which he speaks about the work he has produced during his residency at the BSR from April – June 2023, ahead of the Summer Open Studios.

Part of your PhD project is looking at paintings commissioned in 18th and 19th century by British men to see how Whiteness is self-imagined. Could you tell us more?

To say that there was one definition of Whiteness in the eighteenth century would be an oversimplification of a very complex notion of identity. Whiteness as we in the Western anglosphere might understand it did not exist until well into the nineteenth century. I use the term self-imagination in my doctoral work and my art as a way to reflect the many different ways one could be coded as ‘White’, whether that be through religion, gender, or skin colour. In other words, I want to avoid homogenising a group of very distinct ideologies even though they would be considered the same in today’s racial climate.

For example, Enlightenment philosophers generally supported one of two racial theories: monogenism and polygenism. The former, which was more prevalent until the end of the century, argued that humanity shared one common ancestor and consequent variations in population groups occurred due to environmental factors. Locke’s various texts on the matter, published towards the end of the seventeenth century proved hugely influential on later writers. In Two Treatises of Government, he proposed that ‘there being nothing more evident, than that creature of the same species and rank, promiscuously born to all the same advantages of nature, and the use of the same faculties, should also be equal one amongst another without subordination or subjection.’ These musings on nature were part of a wider argument that inequality is a state of being that was imposed after birth. Locke’s ideas were developed further in the following decades by European thinkers into what we now call ‘Degeneration Theory’, which suggested certain populations had degenerated physically over time due to factors like climate. Buffon, one of the most popular proponents of this theory, believed that Europeans were closest to humankind’s primordial state and indigenous populations in colonised lands were ‘degenerate’ races.

One the other hand, writers like Hume followed a polygenist view on humanity. On the Tartars he writes: ‘the most rude and barbarous of the whites…have still something eminent about them, in their valour, forms of government…such a uniform and constant difference could not happen…if nature had not made an original distinction betwixt these breeds of men.’ What Hume suggests, then, is that while in Europe there existed diverse yet barbarous peoples, there was some intimate connection in their being ‘white’, something that nations of a non-white complexion lacked, for ‘there never was a civilized nation of any other complexion than white.’ In 1723, John Atkins was ‘persuaded that the black and white race have, ab origine, sprung from different coloured First parents’ on a trip to Guinea. Being a colonial naval surgeon, his observations were primarily health-related, and over the course of his career he used medical conditions to formulate his ideas. In The Navy Surgeon, he diagnosed Central African slave populations with ‘Sleepy Distemper’ – today African trypanosomiasis – due to their ‘indolent lifestyles’ and poor diets, something which he believed could only affect these people due to the inferiority of their brains. At the same time in France, Voltaire was coming to similar conclusions, though he was much broader in his racial categorisation. In his early writings he insisted that ‘whites…negroes…the yellow races…are not descended from the same man’, though he fleshed out this idea wholly a couple of decades later.

Even still, being European – or European-descended, or white-skinned did not mean you were ‘White.’ There was genuine concern for the colonisers who moved to the New World and even Ireland, the belief being that they would cease to be White after long enough: reports of Englishmen becoming ‘gay and thoughtless, more fond of pleasure, and less addicted to reasoning’ when they moved to Ireland were contextualised against political aggression against Ireland at the time, and in North America, some Native Americans were ‘milk-white’ in complexion, suggesting that they lacked law and liberty, and, according to William Byrd, the settlers obtained a ‘Custard complexion’ due to their changed diet. Religion also played a part in how White you could be. Charles II was regularly described as having a ‘dark complexion’ due to his Mediterranean Catholic heritage, and travellers to Naples described the ‘common sort’ as ‘a jolly lively kind of animals…more industrious than Italians usually are’ with ‘little brown children’, a combination that was in line with lazy Catholics under the oppression of popery. One writer in 1733 described Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun, who fiercely opposed the Union, as a ‘low, thin Man, [with a] brown Complexion, full of Fire, with a stern…Look,’ similar to the Earl of Perth, with his ‘quick Look; [and] of a brown Complexion.’ Alternatively, Lord Belhaven was ‘a rough, fat, black, noisy Man, more like a Butcher than a Lord.’

While brief, these examples highlight why the idea of self-imaging Whiteness is an important concept to my work. To be defined as White was a cultural definition, following local socio-political understandings of power. The subjects of my art and doctoral thesis may be White in that they are European and have pale skin, but in their own time they were White for a very different set of reasons.

Is the one-year residency in Rome having an impact also in your work as an artist as well as in your work as an art historian?

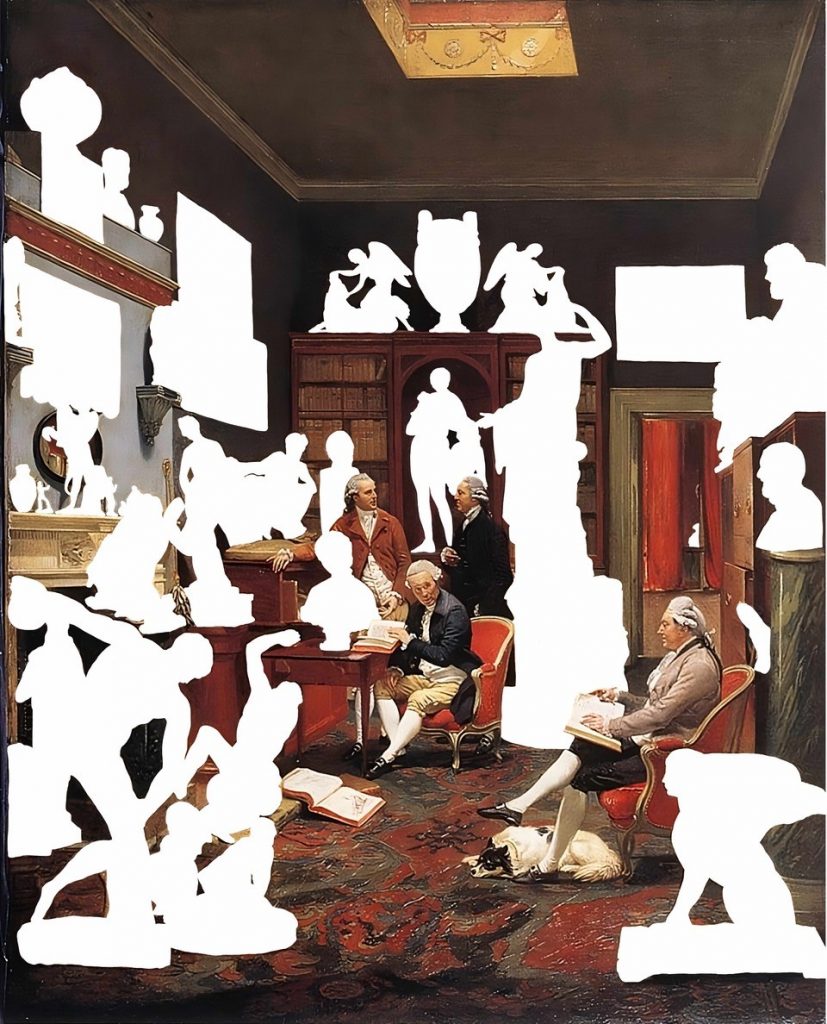

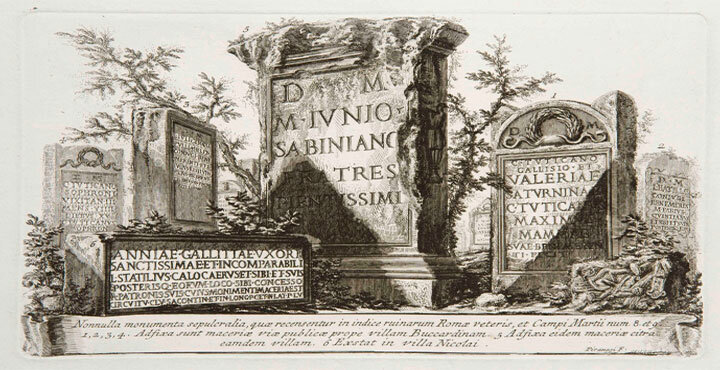

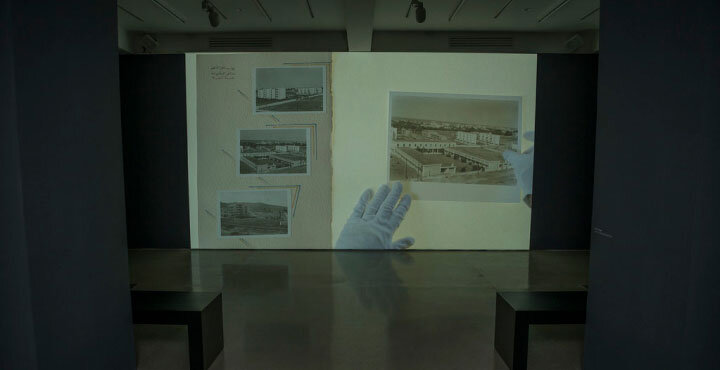

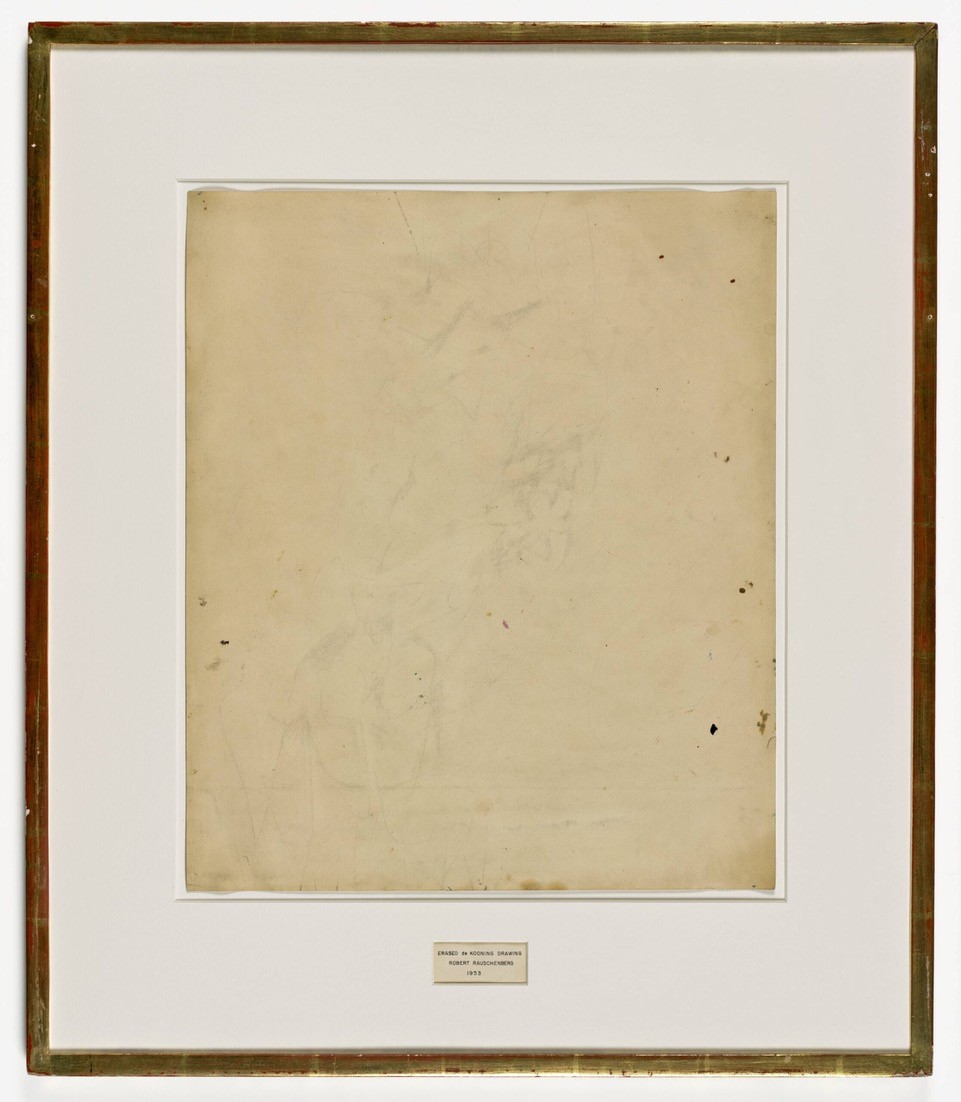

My doctoral research in Rome has had a great impact on my artistic practice, as I am now leaning more towards the aesthetic qualities of whiteness itself as a form of absence rather colour. This shift naturally mimics my research methodology which seeks to interrogate whiteness as a racial category rather than a neutral state. As hooks argues, ‘Often their [white people] rage erupts because they believe that all ways of looking that highlight difference subvert the liberal conviction that it is the assertion of universal subjectivity (we are all just people) that will make racism disappear.’ Up until now my research and practice have explore two sides of the same coin; the former using whiteness as a starting point and the latter using colour. But as my research has progressed, I have begun to feel that using colour on white marble statues doesn’t fully convey the loss of agency that these sculptures have suffered from since being forcefully exported around the world. These sculptures have simply become the object of White desire: ‘White discourse implacably reduces the non-white subject to being a function of the white subject, not allowing her/him space or autonomy, permitting neither the recognition of similarities nor the acceptance of differences except as a means for knowing the White self.’ In this sense, my work explores the ‘activation’ of white marble when it is under a White gaze, for after being placed in a new context it ceases to exist until it is viewed. It is a process of both assimilation and Othering. In Fitzgerald’s words, ‘Do they adorn the modern room or do they belong to another world? The pristine white of the open pages and stockings at the centre of the painting are a measure of the contemporary world’s newness against those yellowing marbles. How do the wigs that elevate the four dignitaries compare to the yellowing marble that signifies the classical status of the statues, or to the natural hair of the ancient busts on the bookshelves, serenely transcending the tangle of figures and groups below? Are the poses of the bewigged men contrasted with, or assimilated to, the poses of the sculptures?’ Thus my artistic practice inverts the self-identified authority that White Britons have prescribed upon themselves over classical sculpture. Their absence is marked in my art, a White void left in their place symbolising both the ideological reality which governs their materiality as well as their role as racial conduits in a White-owned space. Now the marbles are truly White, for they cease to exist, unable to be perceived.