As I already guessed during my first tour of the place, I was quickly reassured that the British School at Rome (BSR, for short) was a unique working environment. Entirely dedicated to research, be it in the fields of history, archaeology, or art, this institution immerses its residents into a particularly pleasant pool of knowledge. And, as far as my experience goes, after more than a month and a half of my internship, the atmosphere is as rewarding for the researchers as it is for the staff that supports them.

As for me, I mostly worked alongside the Library and Archive team. Working under the supervision of a chartiste (a former student of the Ecole des chartes), Raphaële Mouren, are the librarians Beatrice Gelosia, Francesca Deli (known as Franceschina), and Francesca de Riso, and the archivist Alessandra Giovenco. I now take the opportunity to thank all of them very dearly for welcoming me and the wisdom they have passed on to me. Indeed, my internship at the BSR was a meeting between the archives and the library. Both these disciplines led me to accomplish different tasks, but they also confirmed a feeling I had already surmised from previous internships: they aren’t, after all, as different from one another as one might expect.

The biggest mission of my internship was the treatment of the collections, or in technical terms the sub-fonds, of the Archaeological Excavation records, i.e., the archives relating to the archaeological campaigns involving the BSR teams. Most of the documents grouped in this sub-fond (the fonds comprise the much more extensive Archaeological Archive) were produced between the 60’s and the 90’s, and alternate in their nature between journals, catalogues, and correspondence. The archives were mainly written in English, Italian or, more rarely, exotic languages such as French. They are all stored in the archaeology office, locked in metal cupboards or drawers.

Using the word “treatment” to describe my work on this sub-fond is a bit of a stretch: I didn’t have to start from scratch. An inventory already existed, which was written in the 90’s and later revised in 2002. However, I soon realized that between 2002 and 2022 there had been a gap in the archive. After a first quick look at the sub-fonds, it seemed necessary for me to then set up a battle plan. The objective Alessandra had stated was very clear: progress as much as possible in the recording of the archive on Archives Space, the system selected by the BSR to provide readers with an online inventory of its collections. In a word, an online research tool.

But here’s the deal: it wouldn’t have made any sense to put the data online, which I knew to be incorrect, because the inventory didn’t perfectly match the content of the cupboards anymore. Hence it was necessary, before any other job could be undertaken, to do a complete review of the inventory. A tedious task, especially since the sub-fonds includes no less than fifty-nine series, each of them corresponding to an archaeological site. Speaking of which, I should say a few words about the classification of the sub-fonds and its series: the documents were already organized by typology (correspondence, journals, catalogues, drafts for publication, etc.), and I couldn’t see the point of undoing that. It felt like a coherent classification, which respected the different phases of excavation for each site.

As the review progressed, and, having an ever more solid base to work from for an always growing number of series, I could begin phase two of the protocol I had designed: the rough recording of the now checked inventory on Archives Space. A very mechanical work, but relatively fast, that fed the open-source platform with data that could be later reworked to obtain a more harmonious result.

The last steps of my plan, to process all fifty-nine series, I won’t be able to complete for lack of time. I only completed two of them, so they could serve as examples for the person who will resume my work. What will be required is to enrich, according to an established format, the descriptions of each series – a very fulfilling task implying some research – and to refine the descriptions of the documents, adding authority records and information on dates, extent, etc. In the end, when the website will be published – it is now online, but the link isn’t displayed on the BSR website – it shall become a rather efficient and accessible research tool.

Another perspective for the sub-fonds is conservation and reconditioning. Some of the boxes are old, and even potentially dangerous for the documents, as some no longer protect their content. Some of the envelopes are overcrowded with documents and tear when handled. The first step of this job will be to evaluate the precise extent of the sub-fonds. As for the rest, it is a story for another intern to tell!

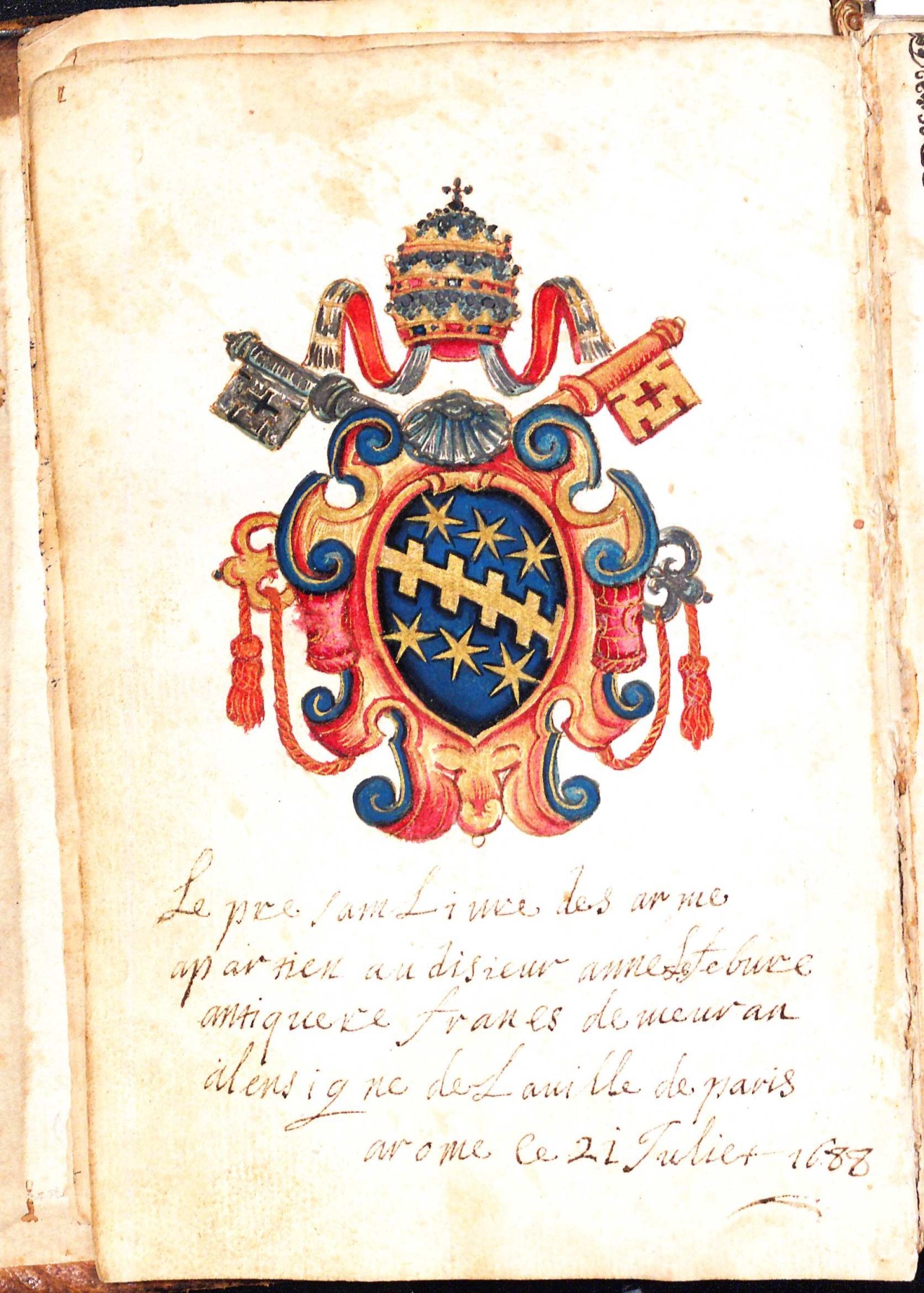

The adventure was very different in the library, but no less diverse. The first mission I was given was the study of a manuscript. Exceptional among the collections of the library, the Ms32 (that’s its little nickname) had been briefly described for the index files but never closely studied. So, I did. It is a manuscript dated to the beginning of the seventeenth century, an album amicorum to be precise, made by Giacomo Lauro, a Roman engraver. In this book, the artist put together the letters sent to him by his most prestigious clients to thank him for his works, to which he added some illustrations in his own hand (mostly coats of arms, but also a small number of painted characters). Passed from one owner to the next over the centuries (including a French merchant living in Rome at the end of the seventeenth century, who thought it would be a good idea to “restore” the book and leave some ex-libris here and there), this small book is rather unusual, very composite in nature, and most of all in a rather concerning state of conservation: the binding, which is almost completely undone, no longer holds the book together, and some illustrations have suffered some damage. Logically, my work was to then take steps to restore and digitize Ms32.

Luckily, I attended a class on codicology last year. I created a record, in English, according to the French norms for manuscripts of the Middle Ages (ignoring some fields that didn’t make sense, such as the transcription of the incipit and excipit). That work pushed me to get familiar with the codicological vocabulary in another language, a task for which I was greatly helped by the library’s resources: farewell then to the réclames, couvertures, and reliure, and hello catchwords, bookplates and, binding. Once the record was complete, I transcribed part of it, with great help from Beatrice, in the library’s catalogue to create an online record for the manuscript.

In the meantime, I also extracted some data from this very rich book. The first thing was a list authors that wrote to Giacomo Lauro. It wasn’t an easy task, since there are no less than 179 letters flooding out of its pages. To a certain extent, the authors were identifiable because of their position: among the first pages we find the pope, the emperor, or the duke of Bavaria. For most, however, I had to be content with a simple transcription of a name, and future researchers will complete the work. I applied the same process to the innumerable coats of arms colouring the book’s pages. It sometimes helped to identify a writer, but it was overall very complicated because most of these coats of arms were Polish. This brought another difficulty to my attention that I absolutely didn’t know about, and specific to the Polish armorial: it only includes a limited number of coats of arms, or herb, that sometimes hundreds of families share. The resources of the library are limited, this time, to a few general manuals of heraldry. I could simply record, for a majority of cases, a description of the coat of arms. That being said, I noticed that there was a lot of creativity in this field in the seventeenth century!

What’s next for this manuscript, which is already ongoing, is a trip to the restoration workshop and then, to digitization. It should soon be available online as a library resource.

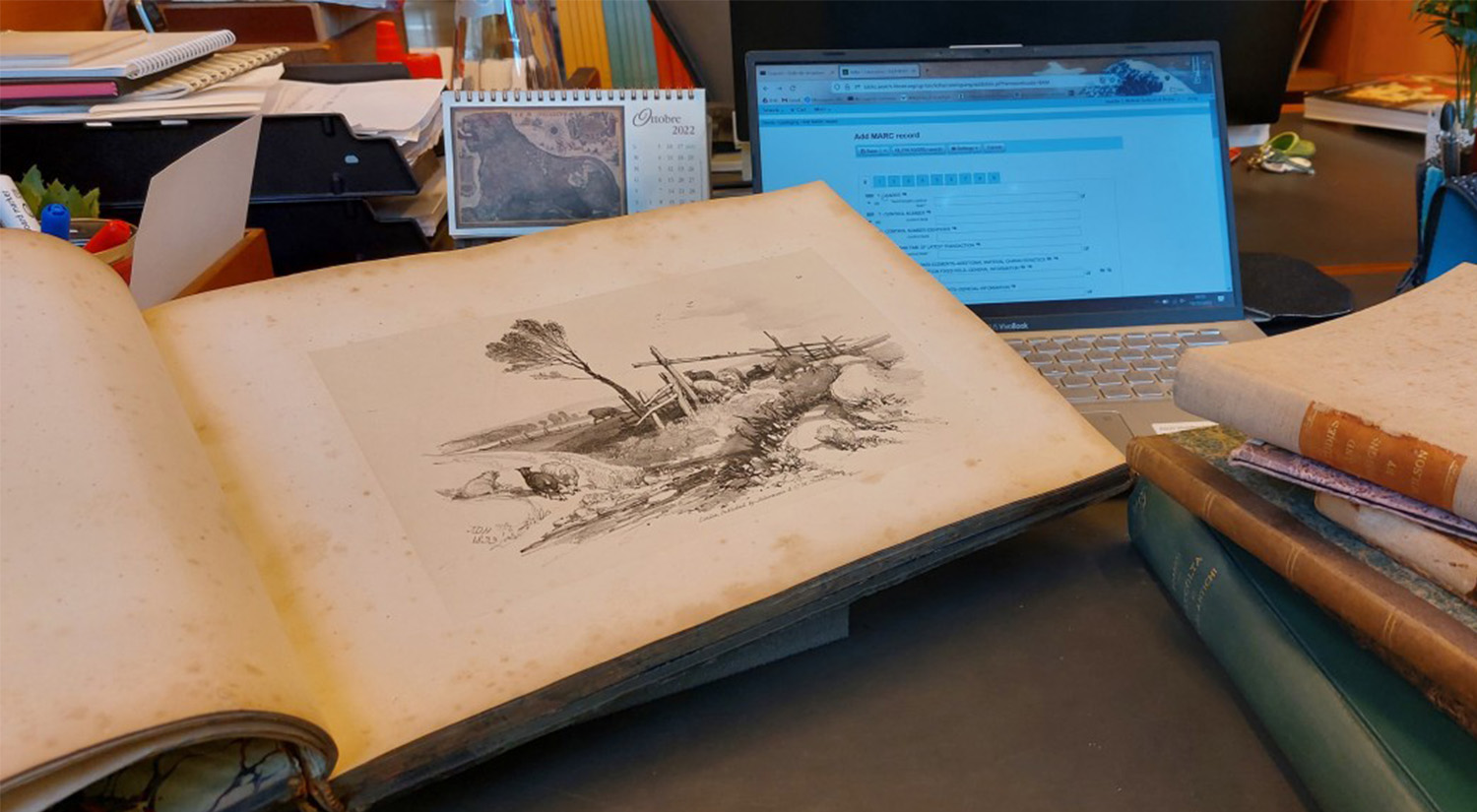

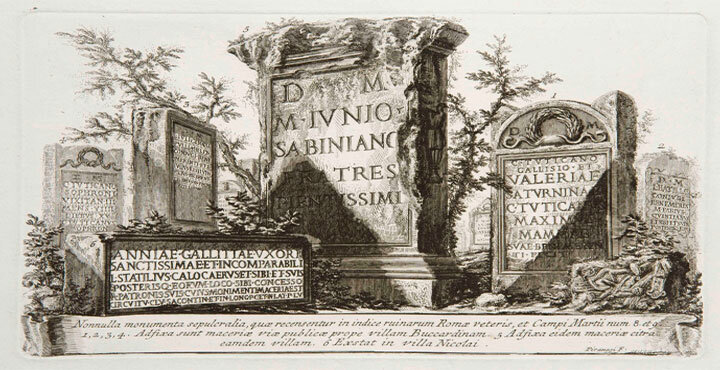

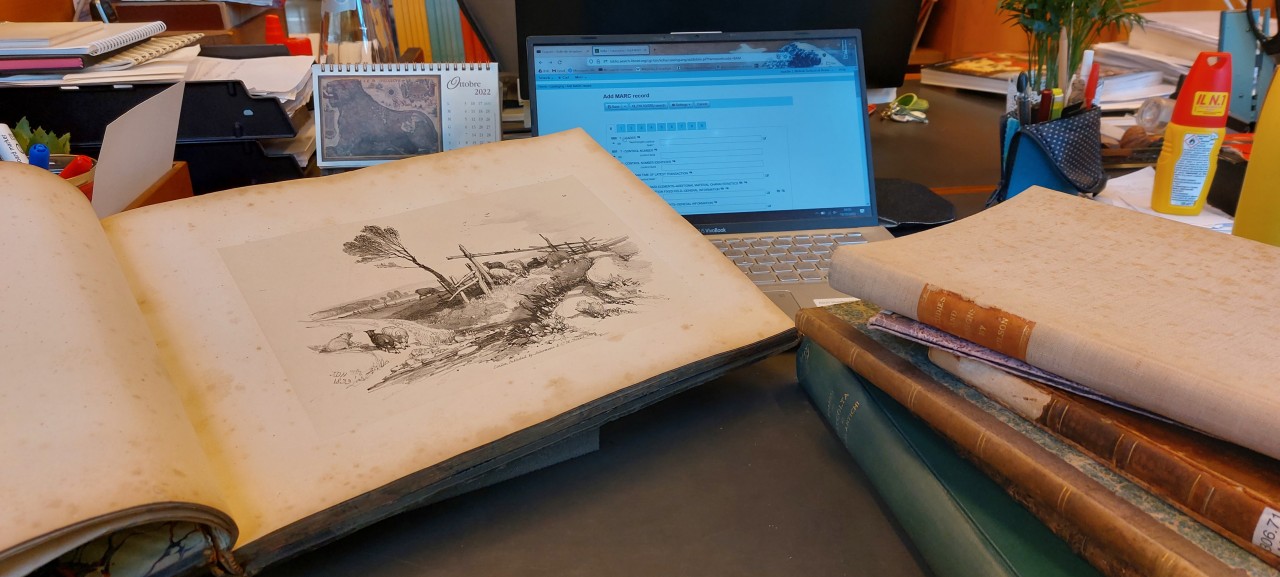

Another aspect of my work in the library was my introduction to cataloguing in MARC. Again, I worked under the very kind supervision of Beatrice, who showed me how to write in this particular language before putting a pile of books, taken from the rare books reserve, on my desk. They are all collections of engravings from the end of the eighteenth or beginning of the nineteenth century, depicting views of Rome and its surroundings, or scenes of rural life. Beyond the pleasure of looking and thinking about these materials (some books are almost tour guides!), I also gained useful experience and familiarity with what is, in my opinion, the essential task a librarian must be able to accomplish.

To conclude in a few words, I would like to repeat myself: archives and libraries aren’t so dissimilar, and they can merge more easily than what my training led me to believe. I found very strong similarities between cataloguing in the library and recording archival material on Archives Space, and identical issues: the identification of authorities, for instance, to create new passageways to information. I would also like to add that the library enriches the work in the archive with its resources, especially when some research is needed, and that the archives, because they include unique documents, are an essential complement to the collection of a library for a researcher. These observations aren’t ground-breaking in any way, but they show the incredible richness of the working environment at the BSR, where the Library and the Archive are only one corridor apart.