An interview with Freya Dooley, Creative Wales–BSR Fellow, in which she speaks about the work she has produced during her residency at the BSR from September-December 2021.

1. You are very interested in the working processes of sound design, and the voice actors/ dubbers in Rome. Much of the work you planned to make is concerned with ideas of illusion, synchronisation, surface, and artifice and how this relates to the embodied and disembodied voice. Can you tell us more about it?

My work spans a range of media and includes writing, sound, moving image and performance. Voice – mine and others’, narrative and literal – is a recurrent theme and material in my practice. My research in Rome has been centered on the politics and history of dubbing in Italian cinema, first utilised under Mussolini as a form of censorship, and subsequent creative and poetic uses of post-synchronised sound and voice in film. Dubbing has expanded as an artform and characteristic of Italian cinema, with some ongoing divided opinion about it’s creative and democratic effects. I’m interested in these relationships between voice and power, and explorations of sonic/vocal leakage and control often come up in my work.

The disembodied voice can evoke many things: implied authority, assumed knowledge, analysis, intimacy… I’m particularly interested in the ‘detached’ voice in the contexts of cinema, politics and radio. Before now I had been thinking about how voice and characterisation in my work can act as a kind of ventriloquism, which I think speaks to dubbing and the idea of layering voices and muting one voice when you introduce another. In Rome I’ve been thinking about scripting for myself and others while experimenting with new soundtracks and recordings.

Experimental post-synchronised sound often reminds you of the mechanics of a film’s making and I enjoy the alternative ways of listening that these exposed layers offer. Dubbing and post-synch can play with the viewer’s suspension of disbelief, and many directors have subverted the practice or play with it as a tool for editing. I’ve been listening to the sound in the films of Pier Paolo Pasolini, whose archive I visited in Bologna recently. Pasolini has a very particular and polyphonic approach to his films and his texts: his soundtracks tamper with the surface of the image and he creates disruptive or surprising sonic relationships between voices, bodies and their environments.

While in Rome I’ve been really fortunate to meet with sound designers and voice artists. I spent time with Sergio Basilli at his foley studio at New Digital Film Sound, and heard about his decades of experience working with directors such as Leone, Fellini and Bertolucci. It was fascinating to see the way foley is used to create the layers of ‘natural’ sound through artificial means: Sergio’s studio is full of a host of strange and mundane objects which can be transformed through small gestures to evoke the vast scale of our environments. His ear is a kind of sonic archive for the ways we move about the world.

I also loved meeting with Silvia Pepitoni, who is a doppiatori (voice actor) who dubbed, among many other characters, Meg Ryan in Italy’s version of When Harry Met Sally. Silvia also directs dubbed versions of films and runs a doppiaggio academy in Rome. She was very generous with her experiences of the industry and passionate about dubbing as an artform: she talked about her relationships to the filmic texts and their translators, vocal personas, and the rhythms and performance of voiceover work which, in many ways, struck me as having a relationship to the rhythms and performance of song.

2. Can you talk about the sounds of Rome?

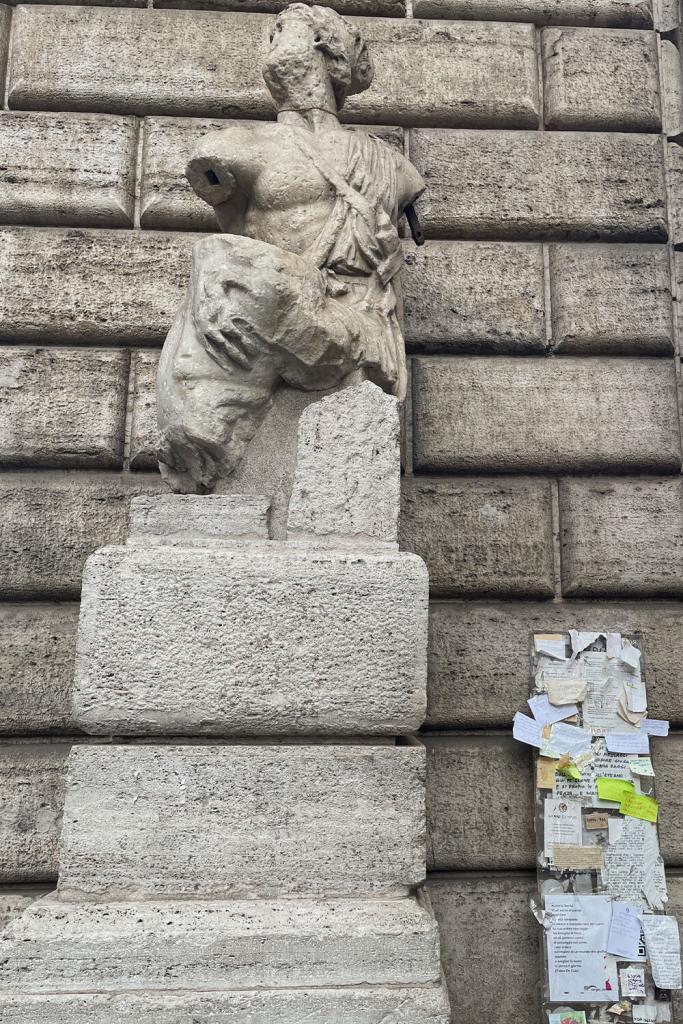

As is usual for the way I work, and as I expected being in a city as rich and intense as Rome, my research has expanded outwards and sideways to think about other forms of voice, text and sound which I’ve encountered here, for example Opera, orchestral and choral performance and Italo-disco music. I’ve spent a lot of time listening during this residency, recording and collecting sounds of the city, from parakeets to public demonstrations: spaces where individual voices commune. I’m also interested in the collected voices at the talking statues of Rome, a group of figures who hold a space for political (and personal) anonymous expression, even today, after hundreds of years.

As part of my practice I enjoy creating intimate or immersive environments for shared or social listening. During the residency I’ve hosted a couple of themed listening ‘parties’ with other Fellows here, where we share music with each other as a way to talk sideways about our research, practices or lives. The sound installation I’ve developed for the Mostra has turned the auditorium – already a space for listening, albeit a different kind – into a kind of awkward school disco, with a soundtrack which merges some of these thoughts about the authority, disembodiment and collectivity of the voice with references to Italo-disco’s typical characteristics of longing, bodies and vocal manipulation.