Abigail Graham is the Course Coordinator of the Postgraduate Epigraphy Course at the British School at Rome. In this blogpost, Abigail looks back at 10 years of the course and pays tribute to the vast contribution to the field made by Professor Joyce Reynolds.

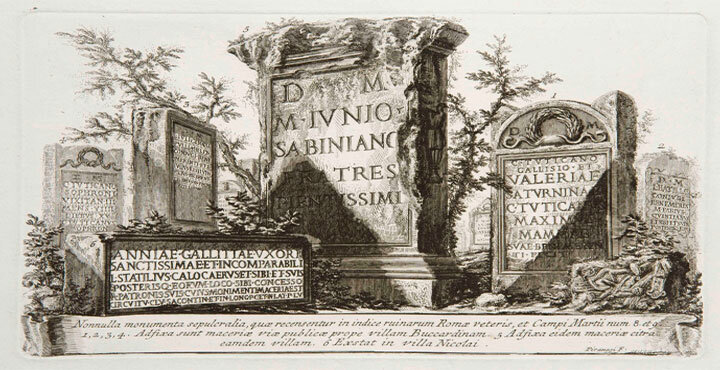

While it can be seen as a niche discipline of history, epigraphy covers a remarkably broad body of material: anything that is “written on”. Inscriptions are not only texts, they are objects in context with imagery, agency and function. Epigraphy occupies a unique crossroads, where literature, history, art, and archaeology converge. Like merging onto a roundabout, these interdisciplinary integrations are not always smooth. Inscribed objects can take us beyond a male elite literary audience, with the voices of women, children, slaves and freedmen addressing a broader, neuro-diverse Roman audience. Inscriptions tell incredible stories, but they also reflect blinkered perspectives, bound by ulterior motives and ideologies. In a way, public inscriptions may have been Rome’s social media: a more ubiquitous and inclusive form of writing, often brief and formulaic in language, employing abbreviations and art that is specific to a particular context and audience. Not unlike my mother trying to decipher her granddaughter’s text messages, my first engagement with inscriptions in Rome (with 5+ years of Latin) was a struggle, which illustrates a crucial point for ancient and modern readers: how we experience writing matters; changing context can result in changes to message, meaning, and audience.

The recent passing of Professor Joyce Reynolds (1918–2022), a legend in the field of epigraphy, was a moment for many to pause and consider the transformation of our field. Although the first BSR postgraduate epigraphy course ran in 2012, the idea was inspired in no small way by Joyce, whom I met on my first visit to Aphrodisias in 2002. I was not her student in a formal way, but through lunches and letters, she played a major role in my academic development. I was one of many, who benefitted from her site trips and annual “Epigraphic Saturday” meetings at Cambridge, where experts and students could present and engage with each other. Joyce was not only educating us about epigraphy, she was showing us how to carry the past into the future: by forging networks, friendships and collaboration through engagement with new materials and researchers. My experiences with Joyce and others, who showed a similar generosity of spirit (Charlotte Rouéche, Rebecca & Al Ammerman, Peter Haarer, Charles Crowther, Roger Tomlin, Silvia Orlandi, and Alison Cooley) together with successful epigraphy courses at the British School at Athens and Practical Epigraphy Workshops (UK), are what inspired the creation of an epigraphy course in Rome.

The British School at Rome is an ideal setting: well situated near Rome’s museums, sites and international institutions. The libraries, archives, permit access, as well as accommodation and classrooms of the BSR, provide a perfect environment for visiting scholars. Behind an impressive and imposing façade, the heart of the BSR is its inner sanctum: a quiet courtyard where golden koi carp skim the surface a tinkling fountain and cosy communal spaces offer a safe and nurturing place, a lovely respite from the lively chaos of Rome. When I proposed a 10-day context-based epigraphy course at the BSR in 2010, the Director, Professor Christopher Smith, was very supportive. The people I met during my first visit, many of whom are still there, welcomed me with open arms into a thriving community of scholars, artists, researchers, and staff.

When planning began, I received a few questions, in particular: was I training the next cohort of epigraphers? Another legendary epigrapher, Louis Robert observed “Regarding inscriptions, two adversities await an historian: not to making use of them or doing so badly.” Both dangers arise from the same problem: not knowing how to engage with epigraphic sources. If only epigraphers have experience with these materials, how will anyone use else them, properly or at all? The BSR epigraphy course seeks to train not only epigraphers but postgraduates across fields. We provide a guide to the crossroads that defines epigraphy by expanding interdisciplinary connections: creating a space where scholars from different disciplines can come together and experience epigraphy hands-on, developing skills, knowledge, as well as relationships with each other and experts in the field. We hope that these experiences will yield further opportunities for collaboration and research, as well as networks of interdisciplinary support.

The resulting course is not for the fainthearted. To complete the journey from discovery to publication and/or display of inscriptions, we spend the first five to six days at an array of sites and museums in Rome and her outskirts (Via Appia & Ostia Antica), leaving the BSR before nine each morning and returning around five in the evening. The July heat can be blistering and some days our walking tour of Rome exceeds 20km. Evenings are for research with some speakers and/or dinner guests. Each participant applies to the course with a research proposal: a specific element that they would like to explore in Rome. Course handouts flag materials for each participant at various sites and museums. The last three-four days offer time for research, culminating in presentations (20 min) on the final day. It is a wonderful way to see how the experience shapes each person’s research and how far interdisciplinary collaboration can go.

It hasn’t always been easy. Two weeks before the first course in 2012, my Achilles tendon ruptured. Christopher Smith graciously offered me the chance to postpone the course, but an image of octogenarian Joyce roaming across Aphrodisias flashed through my mind. We were going ahead. The adversities that I feared most: rolling across Rome in a wheelchair, having to argue in Italian over our permit, getting lost or told off for using the wrong exit or standing too long in front of an inscription, ultimately brought us together, providing choice moments and memories, like carrying a wheelchair up the Capitoline steps in triumphant style. There would be transport strikes, heat waves, lost luggage (2016), 5 days of quarantine (2021) and nail-biting as each site processed our Covid passports, waving us forward into a labyrinth of one-way arrows. Each Rome I meet is different: constantly changing, exposing new experiences and adventures, which require patience, hope, and resilience.

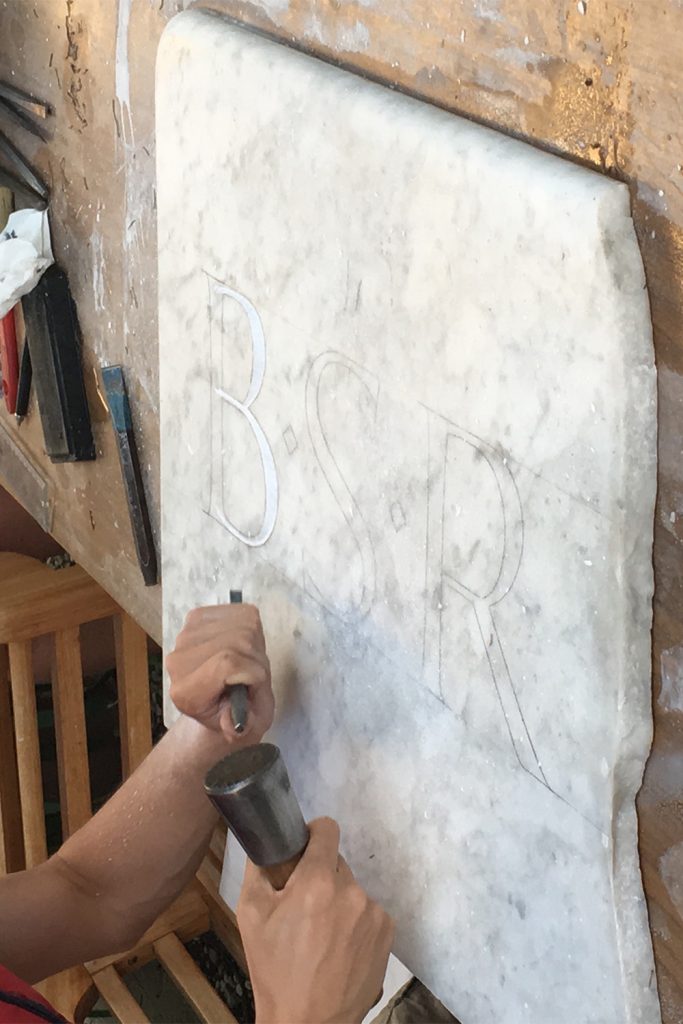

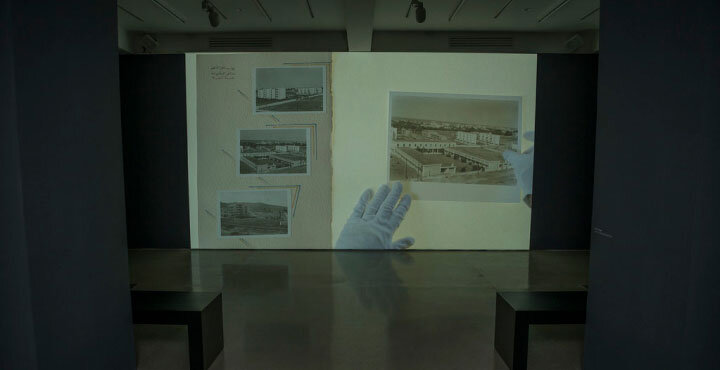

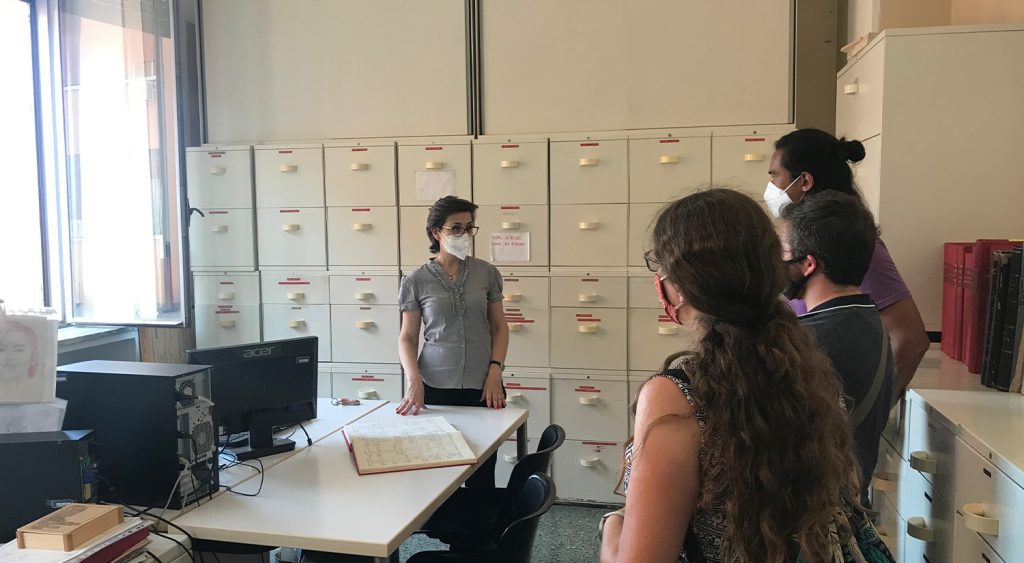

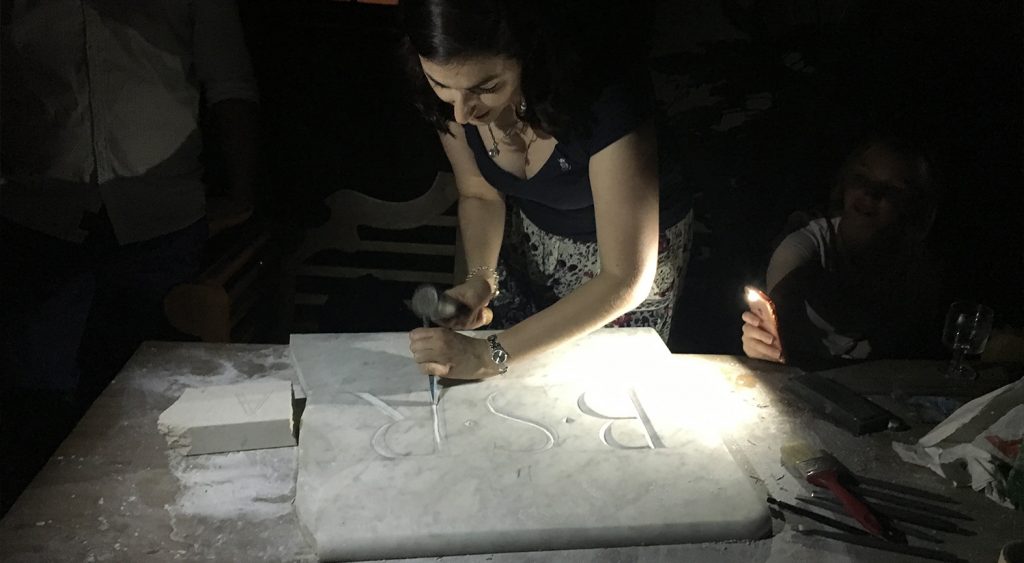

With each passing year, institutional collaborations have grown stronger. Site visits have evolved from brief discussions with curators into amazing guided tours of the collections (Carlotta Caruso, MNR), of archives (Silvia Orlandi, La Sapienza), cast galleries (Francesco Camio, La Sapienza), the Vatican’s Galleria Lapidara (Ivan Di Stefano Manzella) and object handling sessions (Valentina Follo, AAR). Practical sessions have expanded from rubbings and drawings to include photographs, squeezes, searching digital databases and a “live” carving demonstration (2018) video with Wayne Hart, a professional letter cutter, who has carved memorial stones at Westminster Abbey, also let us have a try at chiselling. These improvements were possible because of the generosity of Italian and American colleagues and the BSR, who offer unfettered access to an array of resources, including the marble we reused thanks to Stephen Kay (BSR Archaeology Manager). A favourite innovation has been “Wine, Cheese & Squeeze”, an evening where we invite colleagues and BSR residents to join us in making squeezes of inscriptions in the courtyard, providing a selection of my favourite Italian wines & cheeses. Dining at the BSR with speakers, staff, and residents is also a highlight: an exemplum of how enriching and enjoyable an open & engaged community can be.

Diversity has proven to be a strength on our epigraphic journeys. In the past ten years we have run seven postgraduate epigraphy courses (six public and one privately funded course for a research project), including nearly eighty students from five continents and over twenty countries. Participants, primarily PhD candidates, represent a range of studies: philology, literature, history, archaeology, art history, museums and heritage, film and a professional letter cutter. It has been a truly eye-opening experience. Wayne spotted an inscription from left-handed carver; linguists explained strange archaic spellings; archaeologists revealed an enigmatic inscription was a modern cast; literary scholars found hidden references to poems in epitaphs; art historians uncovered connections between art, text, and gender roles. This year, a participant researched lightning strikes (lightning-struck objects had to be marked and ritually buried). I seldom noticed these inscriptions or the unique symbol for lightning that I now see on many objects: reliefs, coins, buildings, armour, slingshots. Was being hit by a Roman slingshot, like being struck by lightning? If one person can change the way you see the world, imagine what a group of ten can achieve.

The legacy of the course is wide-reaching. Participants have gone on to create and collaborate in numerous research projects, from epigraphic databases (I. Sicily (Oxford), EAGLE (La Sapienza) and ERC projects across Europe. Many of these initiatives are interdisciplinary. A new journal for postgraduate publication “New Classicists” (now on issue 6) began as an idea over breakfast at the BSR. Participants have published, presented and been on the editorial board of this innovative interdisciplinary publication. Relationships and research interests have also resulted in conferences, conference panels (Literature, Ancient History, Archaeology), a new book series (Ancient History), and an edited volume (on Cognition and the Senses in Religion) with Cambridge University Press. Many former participants are also teachers and/or lecturers, and some have returned to the BSR to give conference papers or evening lectures for the course. Others have returned to Rome as award holders: Evan Jewell (2014) won a fellowship at the American Academy this year. Participants have also moved into more diverse fields: film, museums and heritage, as well as foreign diplomacy.

In short, we have not created the next generation of epigraphers. I hope, however, that we have helped to inspire the next generation of thinkers: a broader audience of scholars using epigraphy, who understand the value of interdisciplinary study, collaboration, and the importance of passing on these skills. These are among the most important lessons I learned from Joyce Reynolds; this is how we continue to honour her memory. How we carry the past into the future is not only a matter of teaching history but also embedding experiences, skills, friendships and connections in a new generation. This mission and spirit lie at the heart of the British School at Rome, which has been building bridges of collegiality, creativity and collaboration across academic and cultural disciplines in Britain and Italy for over a century. The next course is set for 2024!!