Sarah Casey, Wilhelmina Barns-Graham Research Resident at the BSR in October 2025, shares in this blog her reflections on her residency experience and the research she will present at the Winter Open Studios 2025 in December.

Before this residency, my recent research had been connected to glacial archaeology – the study of artefacts melting out of alpine ice retreating with global heating. Through this I’d also become interested in other emergence from ice such as mineral sediments, using these to draw. I am fascinated by ideas of preservation – how objects travel through time, their past and future lives, what persists and why? Ice can preserve fragile organic materials that usually decay, and unlike terrestrial archaeology, finds are in flux as ice melts and landscapes shift. I came to Rome wanting to think more broadly about this state of instability and the intermingling of human and geological records.

I travelled here overland via the alps. This enabled me to visit the South Tyrol archaeological Museum at Bolzano, home to some of most famous glacial archaeology finds. The route also placed me in the footsteps of British travellers pursuing their Grand Tours. In fact, my project borrows its title, The Great Departed, from John Soane’s 18th Century description of Rome. While Soane referred to the remains of ancient civilizations, I thought the phase could equally describe the traces of non-human activity.

Arriving In Rome I was able to study historic records of alpine travel: James Hakewill’s sketchbooks and Thomas Ashby’s photographs, both in the BSR’s library and archive. Their drawings and photographs record alpine landscapes that I’d worked in or travelled through vicarious exploration. Holding Thomas Ashby’s glass negatives to the light, I saw black glaciers cascading down pale mountains and spectral forests that glow eerily under a darkened sky. Ghostly images of past environments frozen in time. Recognising the hulking form of Mont Collon, I felt a strange sense of time – intimate and distant at once. The rock flour I’ve been drawing with was once mountain, ground down by glacial action – what mountain or glacier then, might be in my drawings now.

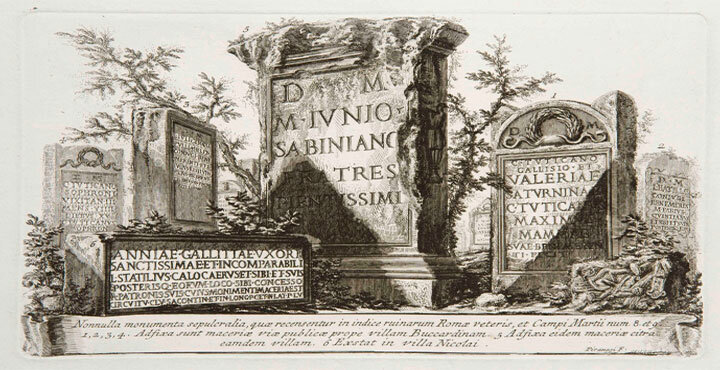

My research in Rome has begun to coalesce around ideas of erosion and deposition. I learn that much of Rome’s ancient architecture was built with pozzolana, a volcanic ash quarried and reconstituted as concrete. The material itself reflects transformation—from ash to stone, from eruption to edifice. I’m piqued by the interaction of human and geologic forces: the Tiber’s floods, accumulation of silt burying the roman port of Ostia and creating the Tiber Island, the extraction of clay and rock and deposits of human detritus. I read that during the Little Ice Age, colder, wetter conditions brought more sediment down the Tiber, reshaping its delta and leaving behind the silt. The valleys between the “seven hills” have are buried under deposits while Testaccio sits atop a hill of waste.

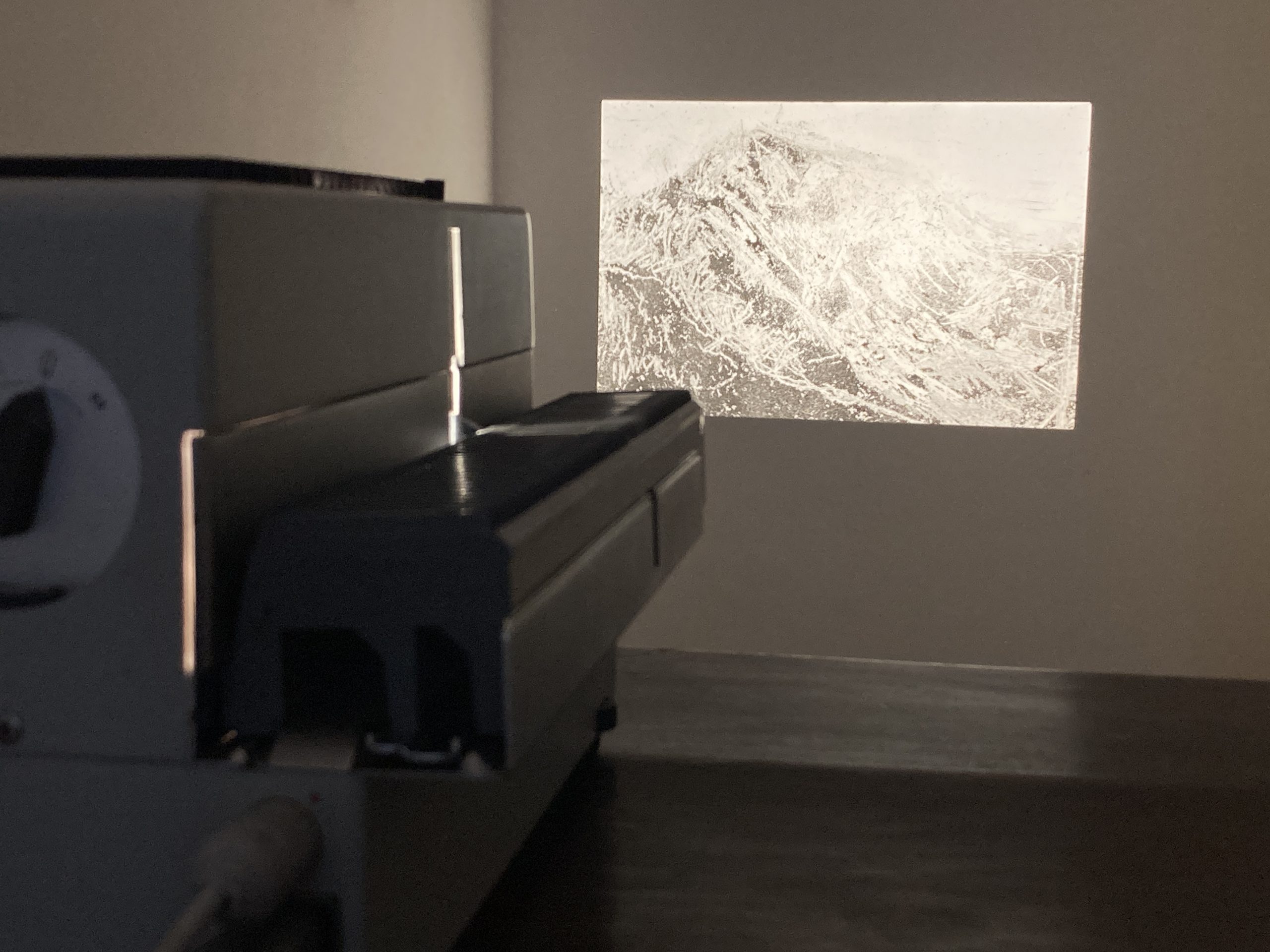

I’ve been collecting sediments, using these to draw, both on paper and as tiny negative space drawings on transparency. I’ve been playing with making these 2x3cm transparencies as 35mm slides to be viewed in an old projector. Their diminutive form seems to resist associations of mountains with timeless grandeur. When projected, the material drawing itself is obscured, instead seen through its monstrous shadow that enlarges my delicate hair- breath marks, and the raw rough, awkwardness of my human errors.

I’ve also experimented drawing with sunlight, exposing drawings of archaeology as negatives, allowing the paper to fade around the image. The process leaves a stain-like trace, which will slowly fade over time, echoing the predicament of ice and unrecovered archaeology.

Like many research projects, I have also been ambushed by unexpected ideas. The fossils trees on display in Verona and garden frescoes at Palazzo Massimo have led to thinking about the botanical ghosts and preservation. While its early days, I have a hunch that these seeds of thoughts might be grown into new works that bring together sediment, light, and time.