An interview with Harry de Vries, National Art School (Sydney) Resident, in which he speaks about the work he has produced during his residency at the BSR from March to June 2024, ahead of the Summer Open Studios.

Could you tell us more about the research you are developing during your three-month residency at the British School at Rome?

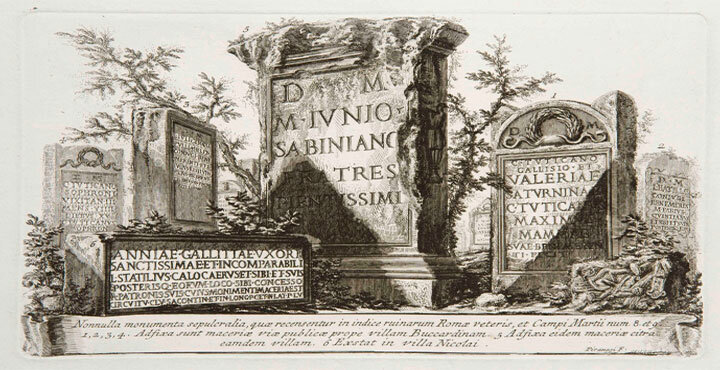

I’m really interested in objects which perform. Rome is full of things which ask us to imagine what they once were or might become, even if all that remains are a few fragments. The past is very visually present here, which makes the performance of objects evident.

For example, I have brought pieces of scaffolding into my studio. Scaffolding is a visual constant in any city. In Rome it takes on a stranger texture. I feel like there’s a tacit agreement that we should look past it and focus on the historical ruins which it supports. It calls us into a kind of contract where we must imagine it invisible; present and necessary but ignored. When it’s placed in a new context, away from the ancient weight of the city, this contract is made evident as the scaffolding is no longer required to fulfill its side of the deal. What new role could the scaffolding perform?

In other places, this agreement is evident from the start. Museums are rife with plexiglass or plaster reconstructions studded with the few fragments of the ‘actual’ object that remain. This has been a constant since the earliest museums. A cursory trip to the Capitoline will show you just how many classical fragments were made into new sculptures during the renaissance. Even many of the most famous Roman marbles are copies of lost Greek bronzes. Rather than display what the object is, we are always called to imagine it’s invisible past. These materials—plexiglass, plastic, bronze, and stone—have been collapsed into new forms in the studio, referencing museological modes of presentation, but detached from any historical referent.

The overriding presence of the past in Rome perhaps masks the fact that the future is as much performed as the past. Rome in 2024 is particularly encrusted with scaffolding and construction in preparation for the Jubilee next year. A lot of this work is infrastructural, but equally, a lot of it is historical restoration and refurbishment for an influx of tourists and pilgrims. The projected future for Rome is one which is even more historicized. This is revealing of the fact that other times are not distant, inaccessible zones, but that the future and past are both equally real and created entirely within the present. Objects are crucial to this work.

Part of the aim of this research is to experiment with how objects might be permitted to take new roles, and these museological techniques of restoration and reconstruction—normally aimed at the past—might be re-tooled to construct the future. It is a practice of ‘fictioning,’ or performing, an alternative future to the one which is prescribed by the dominant order.[1] Scaffolding could be evidence of work recently finished, but it might also indicate work about to begin. Plastic reconstructions combine with stone fragments to represent an object which is yet to exist. As it all collapsed together, distinct temporalities become blurred, and the space between and around the artworks becomes a zone where the future and past are more accessible.

Could you expand on the role of Anthropology in your work? You’ve been influenced by Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropologyby David Graeber and I’m curious to know your thoughts on how an art practice can bridge the active role of anarchy and the more reflective and analytical methods found in anthropology?

Anthropology is a field riven by tensions that arise with trying to produce academic knowledge from subjective, participatory observations. This ‘crisis of subjectivity’ is something which the field continues to reckon with.

Graeber’s Fragments identifies these tensions as a strength. Anthropology could be ‘re-tooled’ towards producing a kind of alternative system of knowledge generation, one which is necessarily subjective, political, and aimed at producing an alternative, ‘new’ mode of being from within the shell of the old.[2]

Comparisons could be drawn here with Legacy Russell’s Glitch Feminism. Both identify these points of breakdown as precisely the beginnings of liberation, as places to search for new, alternative modes of being.[3]

Art, as a mode of research production, is also necessarily subjective, and is able to evade the ‘aesthetic of expertise’ which so characterizes the typical expectations of academic knowledge: the seeking of some ‘perfect’ understanding of an object of research.[4] Rather, art-as-research (specifically art as fictioning) is a pragmatic, action-oriented approach to research which involves instantiating something in the world, rather than simply describing it.

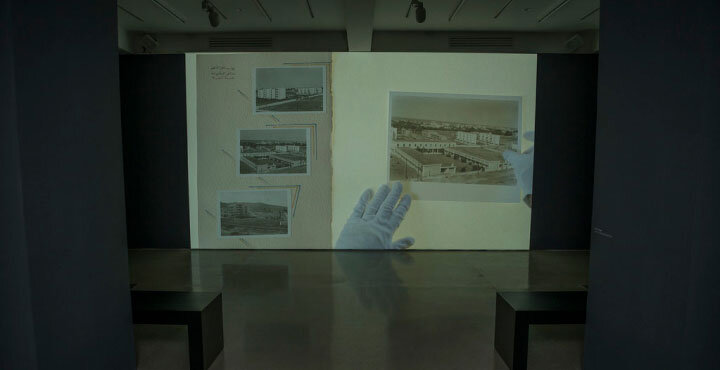

As I engaged with Rome through the British School and my own touristic standpoint, I realised such an approach might allow me to reckon with the decidedly colonial networks that connect Rome and Botany Bay through the legacy of British imperialism. I began to consider my residency a kind of fieldwork, the result of which is not typical anthropological data, but alternative knowledge production in the form of artwork.

This is still an approach which I’ve yet to completely locate. The re-tooling of institutions and seeking out of their fissures and limits is microcosmically reflected in my work at the BSR as I seek to retool materials and objects which reflect these institutions. If anything, the research points towards a kind of No Man’s Land in between art and anthropology— a secret third thing, a kind of hybridized approach which festers in the spaces between more standard academic research or artistic practice.[5]

[1] Simon O’Sullivan, “Art Practice as Fictioning (or, Myth-Science),” Diakron, no. 1 (October 19, 2015).

[2] David Graeber, Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology, 2nd print, Paradigm 14 (Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press, 2006).

[3] Legacy Russell, Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto (London: Verso Books, 2020).

[4] Julie Sauma, “The Body Perfect: On Disability, Experience and the Aesthetics of Expertise.,” Teaching Anthropology 10, no. 1 (August 3, 2021): 71–74, https://doi.org/10.22582/ta.v10i1.591.

[5] Simon O’Sullivan, “Fictioning Five Heads (on the Art-Anthropology Hybrid),” in Five Heads (Tavan Talgoi): Art, Anthropology, and Mongol Futurism, ed. Hermione Spriggs (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2018), 141–47.